By Jimmy Kanonya, community researcher in ACRC Kampala’s Electricity Access Subsidy Action Research (EASAR) project

Informal settlements in Kampala are home to approximately 60% of 2.3 million residents. Despite numerous interventions, access to electricity remains a critical challenge in these settlements. Electricity outages disrupt security and livelihoods. Many inhabitants face barriers to formal electricity connection, leading to widespread reliance on illegal alternatives.

A 2022 report revealed that a significant number of informal settlement residents are participating in unauthorised electricity connections. This practice not only leads to substantial financial losses for service providers but also diminishes government revenues and poses serious risks to the safety and wellbeing of users.

Through our research into the electricity supply and distribution value chains in Kampala’s informal settlements, we are trying to learn more about why electricity subsidies fail to reach those in most need – and the alternatives that residents turn to, in order to gain access to power.

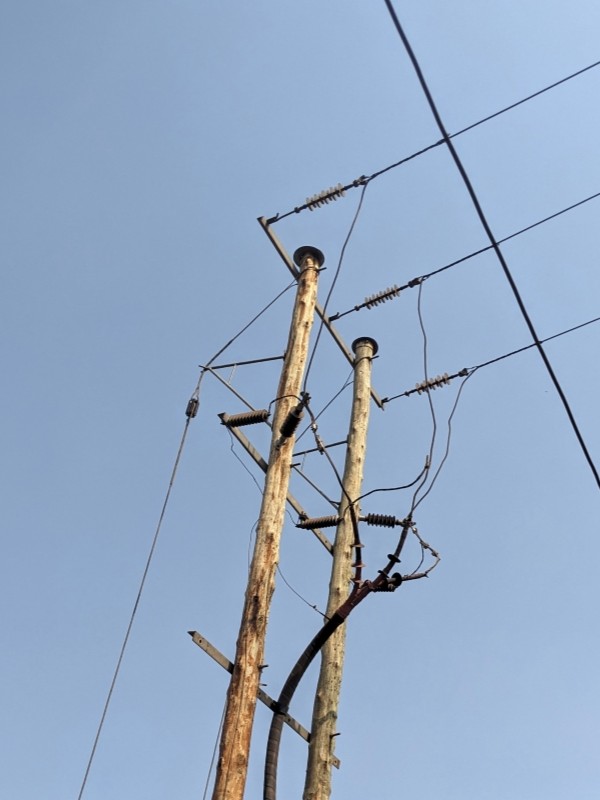

Transmission lines and poles in Kampala

Communities’ experiences with electricity in Kampala

Many residents expressed varying experiences and frustrations when it came to electricity connectivity. Many reported inheriting connections from previous eras, such as during Uganda Electricity Board’s (UEB’s) tenure, only to face disruptions with subsequent providers.

According to some community members, applications for formal connections through Umeme – now Uganda Electricity Distribution Company Limited (UEDCL) – can take months or even years to process, leaving residents without timely access to much-needed power. Along with frequent delays to connection processes, exorbitant costs and discrepancies in unit (tariff) allocations continue to exacerbate electricity access among households.

Besides these challenges, some community members do appreciate progress being made with electricity access, including the installation of prepaid “Yaka” meters, which enhance users’ control of the power.

As residents navigate the complexities of accessing electricity in Kampala’s settlements, some inevitably turn to Kamyufus as an integral alternative service provider.

Besides these challenges, some community members do appreciate progress being made with electricity access, including the installation of prepaid “Yaka” meters, which enhance users’ control of the power.

As residents navigate the complexities of accessing electricity in Kampala’s settlements, some inevitably turn to Kamyufus as an integral alternative service provider.

Kamyufus and their role in electricity access

The term “Kamyufu” refers to a network of informal electricians or illegal connectors who facilitate unauthorised access to electricity. Kamyufus acquire electrical skills through practical experience, such as observing licensed technicians or experience working in the electricity sector. In some cases, they are former employees of utility companies, who were either laid off or have transitioned to independent practice.

Kamyufus are integral to the ecosystem of illegal electricity access in informal settlements. While often labelled as criminals, they are tolerated, protected by the community and even sought after by residents because they address electricity service provision gaps such as delays in electricity connections.

Community perceptions on Kamyufus: Benefactors or opportunists?

Communities hold divergent views on Kamyufus. On one hand, they are criticised for engaging in rentseeking behaviours – withholding information and exploiting vulnerable residents. Their clandestine methods typically involve tapping into existing legal electricity lines or creating makeshift connections without proper authorisation.

However, Kamyufus have undeniably filled a service gap, bridging electricity access to households overlooked by formal systems. Some community members view them as community-embedded helpers, while others suspect collusion with formal entities. This duality underscores the complex socioeconomic dynamics in service provision and access in informal settlements, where necessity often overrides legality.

Challenges and risks associated with illegal connections

The involvement of Kamyufus introduces significant risks. A lack of formal training and oversight means that improper installations have led to property damage, fires caused by poor wiring and even fatalities. Wires are frequently routed unsafely under houses or through trenches, exacerbating electrocution and fire hazards.

In the event of an accident, affected residents often find themselves without recourse through official channels. Due to the undocumented and illegal nature of their electricity connections, reporting incidents could lead to negative consequences. As a result, the cases are swiftly and inconspicuously neutralised. These challenges not only put lives at risk but also create a continuous cycle of inefficiency and loss, for both communities and utilities.

Household connecting wires

Why do communities continue to rely on Kamyufus?

Despite the evident dangers, residents turn to Kamyufus for several reasons. Foremost is affordability – the official costs of formal connections, specifically those without a subsidy element, are prohibitive for many low-income households. Even when subsidy programmes are available, they are often short-lived, limited in scope or hampered by bureaucratic hurdles. Local leaders and those involved in the rollout of subsidy initiatives frequently introduce additional indirect costs, further complicating access.

Efficiency is another driving factor. Kamyufus offer rapid solutions, often completing connections in hours or days, rather than years, which outweighs the perceived risks for those in urgent need.

Information deficits

A pervasive issue exacerbating these challenges is the lack of public awareness about formal electricity access programmes. During transect walks, surveys and focus group discussions in these settlements, it became evident that information dissemination was inadequate. If there were posters or informational displays, they were rarely visible, even in areas where electricity access programmes are active.

According to community members, communication is primarily received via media outlets, which have limited reach, or local leaders, who may lack the education or sensitisation to effectively interpret and relay details. Many residents struggle to explain the origins, purposes or even names of ongoing initiatives, hindering word-of-mouth dissemination. This knowledge gap perpetuates reliance on informal alternatives and undermines electricity programme effectiveness.

A focus group discussion with community members

Electricity subsidy programmes bridging access

Limited awareness about government subsidy initiatives, such as the Electricity Access Scale-Up Project (EASP) and the Wetereze campaign, in areas of implementation hamper access. Often, information disseminated was mixed up, while there were also reports of extortion, exclusion and a limited scope of impact.

In Nakulabye Parish, located in the Lubaga Division of Kampala, some subsidy programmes have seen varying degrees of success. A particularly noteworthy initiative is the Pamoja programme, perceived as an awareness campaign. This programme effectively engaged community leaders in its implementation and facilitated the generation of reports that are widely believed to have inspired the development of subsequent initiatives, such as Yaka and Government Egabudde (government electricity connection).

The Pamoja and Ready Board programme provided free meters, bulbs and electricity poles, with most recipients reporting that these items were indeed provided at no cost. Despite its success, many community members were excluded, due to the programme’s limited scope and time constraints of waiting three to four months for installation.

A lack of clear understanding around the operations of subsidy programmes has limited access and allowed for manipulation. For instance, the government’s Egabudde initiative, often referred to as a “President’s Programme” under Umeme, aimed to provide free connections and meters. However, the programme was plagued by allegations of corruption.

Recommendations for improvement

The mapping exercise revealed a network of key actors in electricity access: residents approach Kamyufus for immediacy, landlords for tenancy-related issues, and politicians for advocacy. Formal offices like Umeme (now UEDCL) are seen as distant and unresponsive, leading to reliance on informal networks.

While Kamyufus provide a pragmatic workaround in the face of systemic failures, their role highlights deeper frustrations with formal processes, subsidies and information gaps. Community members’ aspirations for fairer access through expanded subsidies, zone-based interventions and collaboration with landlords need to be taken into consideration. Subsequently, sustainable solutions in electricity provision must focus on streamlining applications, expanding subsidies and bridging awareness divides to foster inclusive development in Kampala’s informal settlements.

To address these issues, the government and relevant stakeholders should prioritise enhanced awareness campaigns. This could include widespread use of community posters, simplified information materials, and training for local leaders to better understand and communicate about programmes. Revising outreach strategies to ensure clarity and accessibility would empower residents, reduce dependence on Kamyufus and promote safer, more equitable electricity access.

> Read more about electricity subsidy experiences in Kampala’s informal settlements

Photo credits: ACTogether Uganda

Note: This article presents the views of the authors featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

Declaration on use of generative AI: Grok 4 (xAI), accessed via grok.com between October–November 2025, was used to assist with structuring ideas, suggesting phrasing and light editing. All findings, fieldwork data, quotations, and conclusions are the author’s own. The final text was reviewed and approved by the author.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.