In a new open access book, Peasants to Paupers: Land, Class and Kinship in Central Kenya, Peter Lockwood – former Hallsworth Fellow at The University of Manchester and now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Goettingen – tells the human stories behind Kenya’s rapid urban expansion and the families being left behind.

The following edited extract is taken from the book’s introduction:

Mwaura’s story

In early 2017, during the first months of my fieldwork in the neighbourhood of Ituura, where Nairobi’s expanding sprawl meets the tea-growing highlands of central Kenya, I spent practically all my time with Mwaura. Then nineteen years old, Mwaura was the son of my hosts and an unlikely university student from one of the neighbourhood’s poorer families. Sharing a love of football, we spent hours playing an old edition of the FIFA video game series on his second-hand laptop. On weekends, we went to the local “Motel” to watch Premier League football, especially Mwaura’s beloved Manchester United, a team whose then turgid, workman-like style he was always capable of looking past.

For me and Mwaura, our lives of leisure obscured his family’s hardships. Mwaura’s father, Paul Kimani, a fifty-two-year-old long-haul lorry driver, made only sporadic appearances at the family home. The inconsistency of his earnings kept the family in a near-constant state of economic uncertainty. Mwaura’s mother, Catherine, was often forced to cobble together money for Mwaura’s university fees through borrowing from wealthier friends and relatives.

Nonetheless, these months were a time of optimism, the family’s hopes pinned on Mwaura’s fortunes after graduation, the aspirations for him to find “kazi”, formal paid work of the sort that would pay a consistent salary and help them “make it” (kuomoka) to the “stability” of something like middle-class status. With Mwaura stuck on the homestead due to strike action in Kenya’s university sector through early 2017, it was through him that I came to know the neighbourhood, its characters, and pressing dilemmas.

Selling ancestral land

On one of our trips to the Motel to watch a football match, talking during half-time, Mwaura pointed out to me a middle-aged man from Ituura who was making soup for the other guests. Mwaura was appalled by this man’s situation because he was known to have sold a large portion of his inherited land.

“He sold his land for like 7 million shillings in February!”, Mwaura exclaimed. “And now you’re a cook? You’ve finished that 7 million already!? How!?” I was taken aback at Mwaura’s tone of condemnation. At the time, I assumed he was echoing his father’s sentiments. Like other senior men from Ituura, Kimani regularly insisted that selling ancestral land was wrong, tantamount to parental neglect, a failure to pass inherited wealth forward to the next generation. But, as Mwaura’s words pointed out, this very same land was becoming extremely valuable in the shadow of an expanding Nairobi. I asked Mwaura why someone would have sold such a valuable asset. “Some people you can’t understand,” he explained. “They sell their land because they’re poor.” I asked what he had spent the money on. “These ones with short skirts,” he said bluntly, a reference to the women who sometimes accompanied older men to the Motel and were seen to be part-time sex workers.

The speed of expenditure had been shocking. “He was not seen for like four months, and he came back with just 50,000 … Imagine! He was taking taxis around everywhere,” he told me, emphasising the lavish expenditure land sale had afforded this man. “If you’ve got money, how can you walk?” he asked rhetorically. I asked him who had bought the land. According to Mwaura, the buyer could only be identified as “some outsider”.

In 2017, Mwaura’s judgement of this neighbourhood man echoed wider debate taking place across Kiambu about the existential dangers of selling inherited, “ancestral” land. For its smallholder families, the vestiges of a peasantry now working for wages, land is inherited on a patrilineal basis but has been divided over successive generations into smaller and smaller chunks. With shrinking plots, it was becoming increasingly attractive for senior men to sell their family land, sometimes unilaterally, to generate “chunks” of money to cover household debts, to launch small-scale businesses such as chicken rearing, but also, to access heightened lifestyles of conspicuous consumption.

Local commentaries on such acts spoke of the dangers of alienating such family heirlooms, the effects of ancestral “curses” (kĩrumi singular, irumi plural) left by long-dead grandfathers who decreed that ancestral land should never pass out of family ownership. The speed at which land money was spent was often taken to be the kĩrumi at work, destroying the lives of land sellers, turning foolhardy excessive consumption into poverty and destitution. With not an ounce of sympathy, local newspapers condemned the so-called “poor millionaires” of Kiambu County who sold their lands but spent the proceeds on alcohol and women, only to be left with nothing in the end.

Sacrificing the future

What incensed Mwaura that day, however, was not simply that the man in question had made an economic error nor transgressed ancestral wisdom but rather that his act of sale constituted one of fatherly neglect, that he had sacrificed his son’s future by misappropriating the proceeds as much as selling in the first place. “Now he’s not sending his children to school, they’re just idling,” Mwaura continued. “One of his kids is working in that place and he should be in college! Sometimes I feel that I want to slap him. He should have sent his son to college first – then drink!” His intensity trailed off, and our attention returned to the football. Mwaura never slapped the soup-seller, and our attempts to ask him about his land sale at his butchery a few weeks later were met with denial. There was no curse upon his land, and no danger, the man insisted.

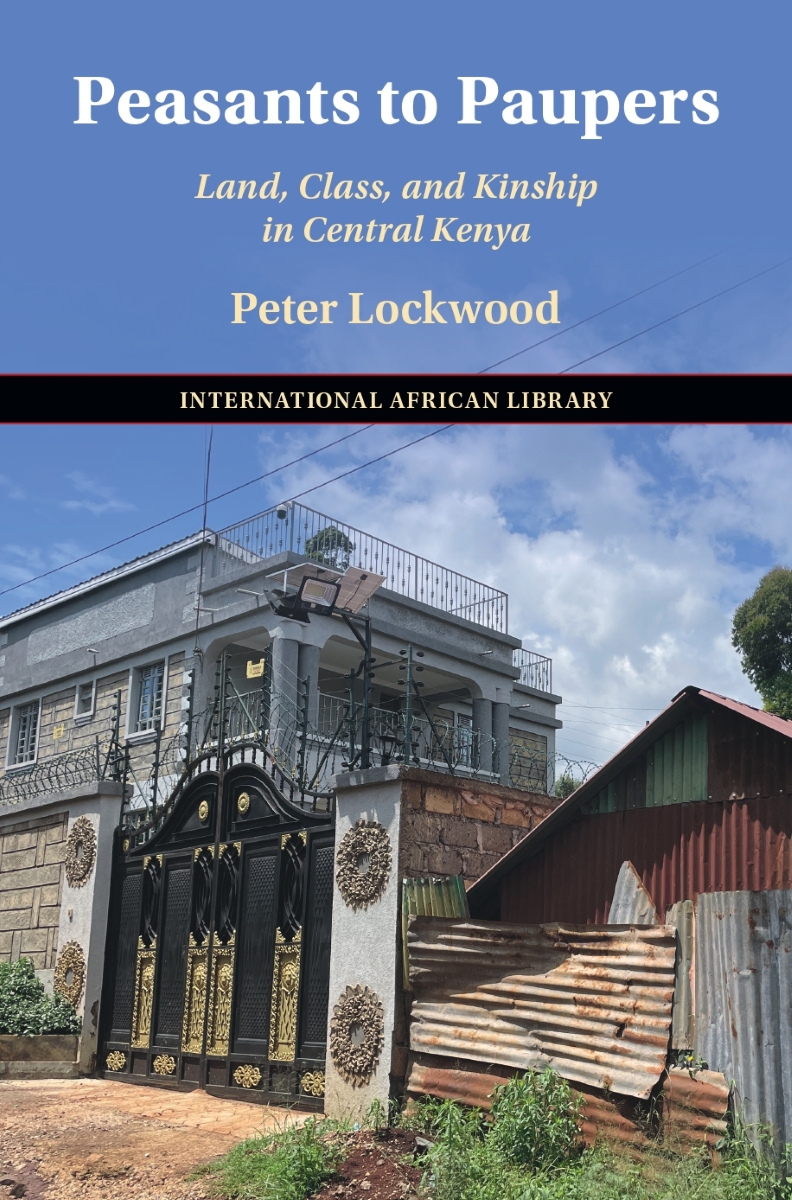

High-rise buildings in upper Kiambu

What Mwaura could have not known then was in a few years he too would be put in the same unfortunate position as the soup-seller’s son. With his own grudging consent, Kimani would sell a large part of his family’s land for millions of shillings, passing on none of the proceeds. In 2022, Mwaura continued to live on his family’s shrunken plot of land, hoping that his father would someday come through with his part of the sale money, while becoming increasingly bitter towards his hypocrisy.

The shadow of Nairobi

The trajectory of Mwaura, my friend and closest interlocutor, across the years between 2017 and 2022 captures a central topic in this book: the fate of Kiambu smallholders as their meagre plots of land skyrocketed in value in the shadow of an expanding Nairobi. In a region already profoundly shaped by colonial histories of land expropriation, Peasants to Paupers explores the terrain of peri-urban Kiambu as the city extends into its poorer northern hinterlands.

Drawing upon my fieldwork with Mwaura’s family, his neighbours, and friends in Ituura over these years, this book illuminates the way an urban frontier encounters a stratified post-agrarian landscape, creating new categories of “winners and losers” amidst the beginnings of a construction boom.

While some smallholder families were building rental housing on their land and becoming landlords, for others the commodification of land created a crisis of kinship as male heads of households sold ancestral land at the expense of their children. Within this urbanising terrain, this book observes the hollowing-out of a moral economy of patrilineal kinship. Despite the insistence of senior men that their land was “ancestral” and therefore inalienable, land sales took place, uprooting families, depriving children of their inheritances, and accelerating a region-wide process of downward mobility as younger generations contemplated their fate as a new class of landless and land-poor paupers.

Masculine breakdown

Peasants to Paupers traces the effects of this process by exploring a wider loss of confidence among young men in the moral horizon of patrilineal kinship and its emphasis on working towards the future by returning wages to the homestead. Faith in this vision is being eroded on the one hand by the grim economic terms of the peri-urban informal economy, with low-paying jobs that operate on a piecemeal basis.

But confidence in a normative vision of masculine responsibility is also undercut by land sales themselves – experienced within patrilineal families as acts of moral transgression that render young men like Mwaura doubly hopeless, contemplating his father’s betrayal of kinship’s future-orientation and the principles of passing on wealth.

Such overt practices of private accumulation served to compound a sense of patrilineal kinship’s breakdown when they came at the cost of others. It was not only senior men who were seeking to escape poverty through land sale. Amidst rural destitution, young men were seeking desperate and piecemeal attempts to cope with hopelessness about their futures through drinking alcohol. Meanwhile, young women were cultivating extra-marital relationships with wealthy “sponsors” precisely because their male peers were “wasting themselves”. Knowledge of such relationships further entrenched male distrust of women’s intentions, undermining the ideal of the harmonious patrilineal household, and fomenting a gendered self-perception of male abjection.

Against the backdrop of an eroding belief in the achievement of patrilineal household, Peasants to Paupers explores how Kiambu’s young and poor cope with their downward mobility. It charts their challenging journeys as they ward off hopelessness, struggling not to become “wasted” like their alcoholic peers. It draws out the moral debates taking place on the economic margins about whether work can materially provision a reasonable middle-class future. These debates reveal the limits of a bootstrap mentality of labour’s virtue under conditions of wage-limited precarity. While some manage to maintain their hopes for a better tomorrow, for others the grim realisation that they will never meet their aspirations prompts a deep hopelessness and a “giving up” on the future.

In highlighting these themes, this book argues that Nairobi’s expansion is driven not only by the outward push of an urban frontier but by the vulnerability written into the city’s rural hinterlands by the region’s colonial and post-colonial history. The urban frontier’s “expansion” can just as easily be seen as a “retreat” for Kenya’s peri-urban post-peasantry, no longer able to maintain the moral economy of patrilineal kinship and keep the family tethered to land. In such a changing landscape, this book argues for the study of kinship’s moral economy as a critical field, especially as scholars of an urbanising Africa begin to explore the way expanding cities shape their once-rural hinterlands.

Across the globe, enormous numbers of people’s lives are defined by their access to land, which is in turn mediated by kinship. In such settings, kin relations themselves become central mechanisms in the creation of new class distinctions, shaping economic fates across generations. This book closes by calling for a return to studying the imbrications of class, kinship, and landed property.

> Read the full, open access version of Peasants to Paupers by Peter Lockwood

Photo credits: Peter Lockwood

Note: This article presents the views of the authors featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.