By Ahimbisibwe Paul and Elisha Seddugge, researchers in ACRC Kampala’s urban youth action research project

Across Uganda, awareness of government youth programmes – such as the Parish Development Model (PDM), Emyooga and various livelihood initiatives – is impressively high. Yet youth participation remains stubbornly low.

These programmes are primarily aimed at improving young people’s skills, as well as increasing access to economic and development opportunities. Our recent study sought to understand why knowing about these programmes does not necessarily translate into active participation.

The information gap: Awareness without access

Our study findings show that the flow of information about youth development programmes is multi-layered and often indirect. Instead of reaching young people directly, information travels through multiple intermediaries – including local leaders, community agents, peers and social networks. While this structure helps to ensure cultural and community legitimacy, it also slows down the flow of accurate and timely information.

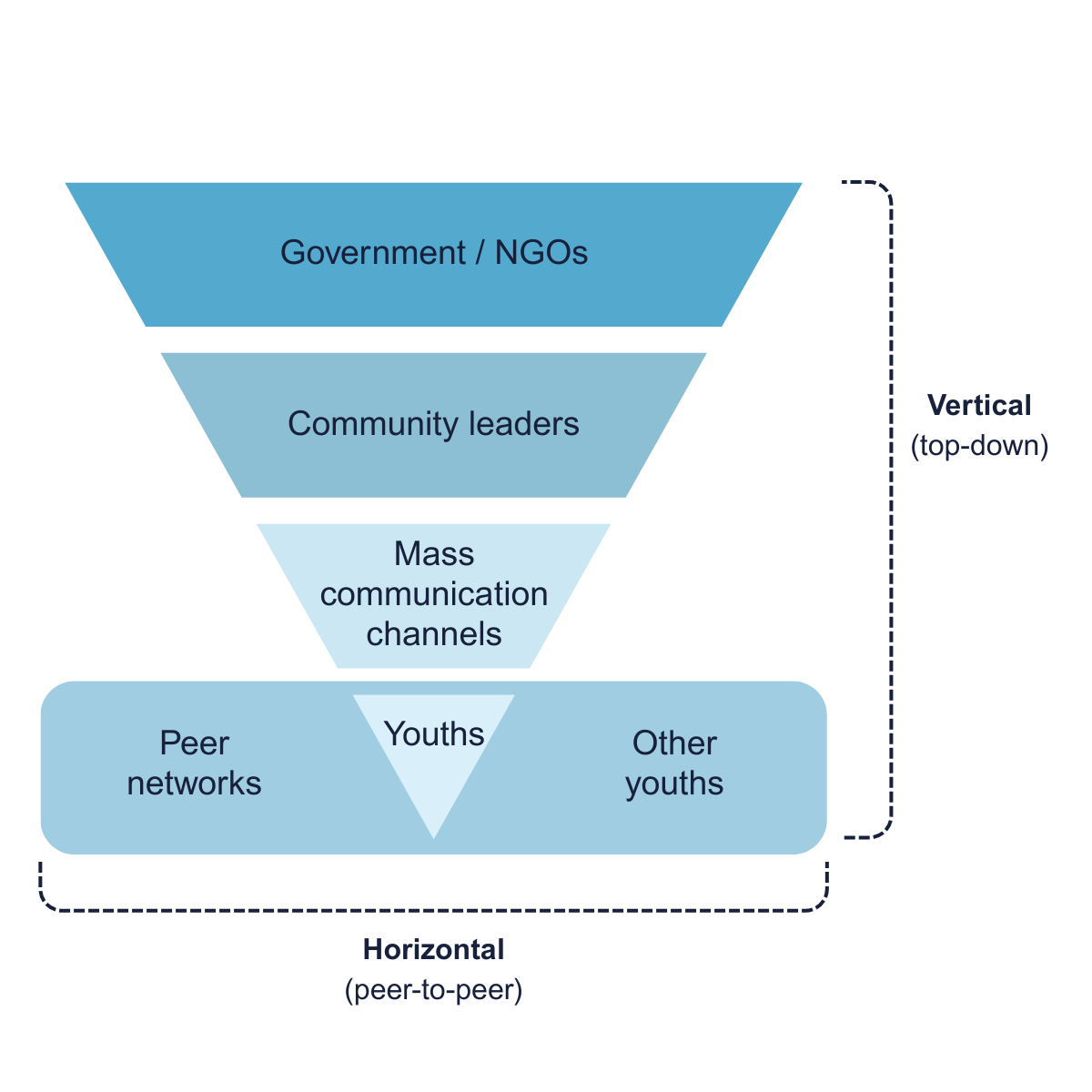

We identified two main information pathways: vertical (top-down) and horizontal (peer-to-peer). For a clear understanding of the gap, the layers can be categorised within these two pathways, as presented in the figure below.

Hierarchical information flow pathways on development programmes among youth

The vertical (top-down) pathway

Information usually starts with programme implementers – government agencies, such as the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) and the PDM Secretariat, and non-governmental actors like Uganda Youth Development Link (UYDEL), Tiko and religious institutions. These institutions rely heavily on local community leaders – local council youth group leaders, religious and cultural heads – to relay messages to their communities.

This approach leverages trust. Local people tend to believe their community leaders more than outsiders, as one female programme implementer explained:

“When we have outreaches, we reach out to the local and youth leaders first. They understand their people, and when they speak, the youth listen. Otherwise, if they don’t know you, they think you’re a mufere (conman).”

Community members echoed similar sentiments during focus group discussions:

“We normally get this information through our chairman or church leaders – they always tell the truth.” (Female, Katwe)

“Our youth councillor told us about the skilling programme. He came door to door looking for girls interested in tailoring, bakery and hairdressing.” (Female, Kisenyi)

While this process builds legitimacy, it also limits reach and speed. Information is often shared using megaphones, community radios or word of mouth, which are effective but time-bound and localised. By the time information reaches many young people, deadlines have often passed or details have become diluted.

As one focus group respondent put it:

“There is a lady who moves with a megaphone passing information. Whenever she does, we know it’s true – but it happens rarely.” (Female, Katwe)

The horizontal (peer-to-peer) pathway

The peer-to-peer or horizontal information flow occurs when young people share opportunities among friends, neighbours or group members. This method is fast, informal and widely trusted – especially when it happens via WhatsApp groups, phone calls and everyday interactions.

“It’s my friend who told me about the programme. We look out for each other.” (Male, Ggaba)

This pathway is powerful for spreading awareness, but less reliable for detail. Information is often incomplete, outdated or distorted by the time it circulates widely. As a result, young people may know that a programme exists, but lack the “how, when and where” needed to participate effectively.

Why awareness does not equal participation

The study concludes that the bureaucratic, multi-layered communication chain is the biggest barrier. By the time information trickles down from implementers to the grassroots, it is often late, diluted or missing key details. Youth at the “bottom” of the chain end up hearing about opportunities that have already passed.

Furthermore, structural barriers – such as political patronage, corruption, illiteracy and digital exclusion – limit equal access to credible information. The reliance on intermediaries makes it easy for gatekeeping and misinformation to thrive.

The way forward: A centralised and inclusive information platform

Both vertical and horizontal pathways are important, but they should be complemented by a centralised, transparent information platform – such as a digital or community-based ‘youth opportunities portal’. Such a platform would enable all young people, regardless of background, to directly access up-to-date information on available programmes, eligibility criteria and deadlines.

A centralised system could also minimise political interference, ensure inclusivity and build trust between implementers and young people. Only then can high awareness translate into meaningful participation – and Uganda’s youth realise their full potential as agents of sustainable development.

Header photo credit: Zach Wear / Unsplash. Young people playing basketball in Uganda.

Note: This article presents the views of the authors featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.