By Adewumi Badiora, ACRC Action Research Lead, Lagos

As Africa’s most populous city – with a current population of over 25 million – Lagos is not alone in having a public infrastructure shortfall. When it comes to streetlighting in particular, Lagos has an extreme deficit. Most roads in the city’s residential areas are dark. And where public streetlights have been provided, many are now defunct, while others have begun to go out due to age and poor maintenance.

It has become a huge and increasingly unsustainable challenge to power streetlights in Lagos – either through conventional power generation, linking to the national grid, and/or providing diesel or gas to power them. They are also subject to vandalism. This makes movement at night dangerous in many parts of Lagos, leaving a majority of residents, particularly women and girls, feeling vulnerable and exacerbating their fear of crime.

The situation is even worse in informal settlements. Many of these areas have never been lit, despite the fact they are home to a significant proportion of the city’s population, with over 200 such communities identified in Lagos.

Understanding safety and security in Lagos

The ACRC team conducted safety and security domain research in Lagos to understand local perceptions and experiences of crime and insecurity. This research shows that in the last five years, everyday crime – such as armed robbery, assaults, thefts, cultism and banditry – has been on the increase in Lagos. Most of these crime incidences occur in the night or early morning.

There are several drivers and enablers of crime, including urban design issues – such as the porosity of city boundaries and inadequate provision of infrastructure like streetlighting – as well as an increasing rate of uncompleted and abandoned properties. Findings show that the increasing number of crime hotspots in Lagos was due to the poor nighttime environment.

Streetlight installations therefore seem to offer the potential to deter crime, as well as provide other socioeconomic benefits to the city. The question now is: could streetlights actually prevent crime and contribute to sustainable livelihoods for residents?

Danfos (minivan taxis) are a popular mode of transport in Lagos. Photo credit: peeterv / iStock

Evaluating the impact of streetlighting

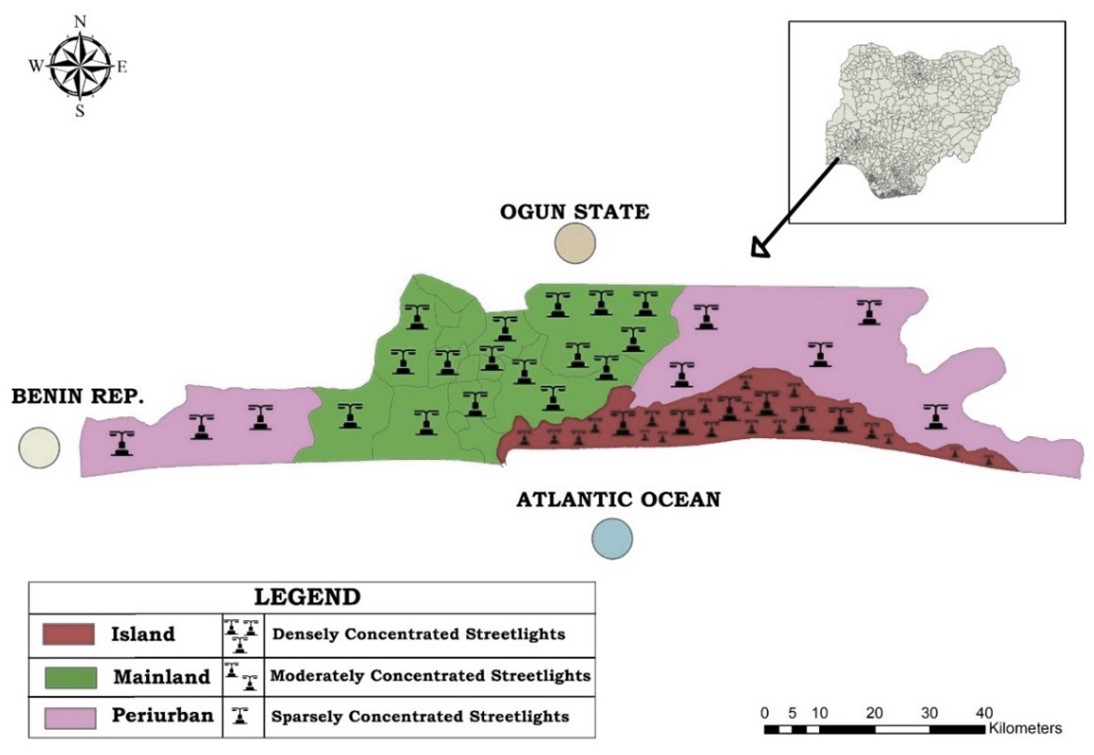

Explorative research was carried out with residents of Lagos communities along the city’s main geographical areas – Lagos Mainland, Lagos Island and the peri-urban areas of Lagos – as well as with the city’s key stakeholders, including state, non-state, security and academic institutions.

Interestingly, economic and social benefits were particularly prominent in the research findings. Residents feel safer going out after dark when streets are well lit, while workers feel safer walking to and from their homes early in the morning and at night.

Businesses on newly lit streets have seen increased revenue as a result of being able to operate for longer after nightfall. A small-scale business owner on one of these newly streets said: “Streetlighting has changed my business operations. I can now operate for more hours without fear of intimidation by the area boys. I now have higher incomes.”

A previous case study, focused on the impacts of solar-powered lighting in Kampala and Jinja in Uganda, established that extending trading times beyond daylight hours could add tens of thousands of working hours daily to the economy. Such an increase in productivity was highlighted by another Lagos respondent in our research, who said: “I have seen a tremendous increase in the number of people that patronise my goods beyond daylight hours. Because of this, I have to employ another sales attendant to be able to handle this increase.”

Another respondent commented: “Policing work is now better in the night and we do not necessarily need to rely on battery-powered torchlight in communities.”

Streetlighting can evidently lead to a variety of socioeconomic benefits, such as lower crime rates and a more vibrant nighttime economy. However, these impacts are not currently being evenly felt or enjoyed across the city, with power and politics playing a significant role in who benefits.

Streetlighting along Lekki-Ikoyi Link Bridge in Lagos. Photo credit: Tunde Buremo / Unsplash

Narrowly concentrated streetlight infrastructure

Highlighting the quid pro quo of public lighting infrastructure in Lagos, our research findings show that streetlight provision and maintenance by the state could at times be related to patronage politics or client politics, used to garner community or residents’ votes and/or reward community political support. But informal settlements do not always have the capital and political pull to attract infrastructure, unlike the areas where city elites reside. Hence, we found the provision of streetlight infrastructure to be narrowly concentrated – orientated to benefit elites’ neighbourhoods.

As one resident explained: “The people in power only fix streetlights where it benefits them. When you are a minority or in opposition, you get scraps or even nothing. The criterion of distribution that the people in power use is simply – did you or will you support me?”

Nevertheless, many disadvantaged neighbourhoods have been able to install and continue to preserve their lighting infrastructure through community self-help, philanthropic gestures of individuals, and partnerships with non-governmental and civil society organisations. According to one resident, the very few streetlights provided by the state are “foni ku, fola dide” (epileptic) – due to negligence and lack of maintenance effort from the provider (state), as well as a lack of involvement from the community at the project inception, making it impossible for the community to own most of the state-provided streetlighting. But the Lagos “Own your Street Light” initiative is gradually changing this narrative in some places.

Figure showing the spatial concentration of streetlight infrastructure in Lagos.

Credit: Mark Awolola (research assistant for the Lagos Streetlight Assessment).

Tackling inequalities and maximising safety and socioeconomic impact

Our research has shown a variety of socioeconomic benefits of streetlight infrastructure and the lack of attention paid to informal settlements. Because of their lack of political capital, finance and other forms of social support, informal settlement communities face multifaceted deprivations.

Tackling these challenges entails a multidimensional approach, which ACRC action research and other future interventions should consider:

1. Approaches and principles must be people-centred, with stakeholders driving change. Ensuring that a diverse range of actors, including local communities, are involved in planning and implementation will help to maximise social impact and economic returns, as well as supporting bottom-up maintenance and management.

2. Interest should be garnered from state actors and other elites, so that the approach and implementation can be scaled up to other communities. Engaging community members who have developed skills in streetlight installation will also create employment and knowledge spillovers, enabling lighting technologies to be rapidly scaled up. These should be supported by capacity building for community members and local governments, for improvement in project delivery, maintenance and budgeting capabilities in order to deliver scaled-up, sustainable public lighting infrastructure.

3. Alternative and sustainable solutions should be prioritised to overcome challenges posed by the energy crisis, limited public finance and, crucially, the limited maintenance funding available to residents of informal settlements. A total transition to solar-powered streetlights could be the best option. One sub-Saharan case study has shown that installing and maintaining solar-powered streetlights instead of conventional options could reduce upfront installation costs by at least 25%, streetlight electricity consumption by 40% and maintenance costs by up to 60%.

4. Solutions should consider longevity and resistance to vandalism, through the use of technical innovation, durable materials and impact-resistant features. Additional security measures, such as attaching special patrols to the streetlight facilities, should also be factored in.

Having completed the foundation phase research on safety and security, as well as the explorative research evaluating the impact of streetlighting on safety and socioeconomic activities, ACRC Lagos is currently planning a streetlighting action research initiative. This aims to answer various questions related to streetlighting, covering reach, cost, quality of facility, maintenance, impacts and sustainability. These answers will be crucial for scaling up the intervention.

Together with residents, NGOs and community organisations, we aim to boost safety and socioeconomic activities by co-producing lighting strategies to improve life after dark in Lagos. Collectively, we will be working in the informal settlement of Ajegunle-Ikorodu. By forming a community of practice through our action research project, we will be able to learn, grow and form an evidence base aimed at influencing streetlighting policy specific to informal settlements, supporting local initiatives and encouraging community-driven efforts to strengthen the public lighting programmes.

We will be incorporating the above four key issues that require attention in streetlighting solutions for our project. We hope that this will garner interest – especially from the state and elites – so that implementation can be scaled to new communities through the community members who will develop skills and capacities through our action research project. This is a very exciting initiative and has much potential for scale.

Header photo credit: peeterv / Getty Images (via Canva Pro). Lekki-Ikoyi Link Bridge in Lagos, Nigeria.

Note: This article presents the views of the authors featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.