Guest blog by Felix Agyemang, lecturer in spatial data science at The University of Manchester, and Sean Fox, associate professor in global development at the University of Bristol

According to UN estimates, the global urban population will increase by 2.5 billion over the next three decades, and 90% of this growth will occur in Africa and Asia.

Africa alone is projected to absorb close to a billion additional urban dwellers by 2050. This urban population boom will lead to rapid physical expansion of existing African cities. Managing this growth effectively is a monumental challenge.

A key to getting it right is understanding likely patterns of future urban expansion. This is one of the many shared challenges facing the African cities that are members of the Africa-Europe Mayors’ Dialogue, a platform coordinated by ODI that brings together over 20 African and European cities.

Why modelling urban expansion is critical for sustainable development

Being able to predict the likely locations of future urban developments can help urban and regional planners to anticipate infrastructure needs and prepare better land use and local plans to promote sustainable development. If we can successfully predict patterns of urban expansion, our cities can grow more sustainably. Two main modelling approaches have been developed to predict patterns of physical expansion in cities.

The first is a geophysical simulation approach known as cellular automata (CA). The most popular and widely used CA model has been SLEUTH, which was developed in 1997 in the US by Keith Clarke and his colleagues. SLEUTH is an acronym for the input data (slope, land use, exclusion, urban, transport and hill shade) required to apply the model. It has been widely applied for planning purposes in cities in the global North. Academics have applied the model to some African cities, including Lagos, Nairobi, Yaoundé, Cape Town and Accra.

But SLEUTH, like other CA-based urban expansion models, has a critical limitation that is particularly important in Africa: it doesn’t model the social processes that drive spatial patterns of urban expansion. These processes can differ significantly across regions.

A dominant feature of African urbanisation is the highly informal nature of most new neighbourhoods and developments. Informal urbanisation is characterised by households self-building on an incremental basis without formal planning consent, often in a context of ambiguous or insecure property rights. This is unlike in many parts of the world – especially the global North – where real estate developers build housing that has been formally approved on land that has a clear chain of ownership or occupancy rights. Individuals or households then buy, lease or rent these units within a transparent regulatory environment. SLEUTH works relatively well in the latter context, but not within contexts of informal urbanisation.

The second modelling approach that has been developed more recently is known as agent-based modelling (ABM). An ABM has the advantage of incorporating the behaviour of diverse actors responsible for change in an urban system. One of the attractions of ABM is the ability to model urban land market processes, such as individual preferences, competition, relocation, and resource constraints that underpin residential location choices. There have been a few applications of ABM to informal urbanisation in Africa – including a slum area in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Shama, Ghana – but the accuracy of these models has yet to be confirmed through rigorous validation.

A new urban expansion model for African cities: TI-City

Bringing together both modelling approaches, we developed a new model known as TI-City (the informal city). TI-City is designed to predict the location, legal status and economic status of future residential developments in African cities. Importantly, it was specifically designed with the realities of African urban land markets in mind – especially the informal nature of most new developments.

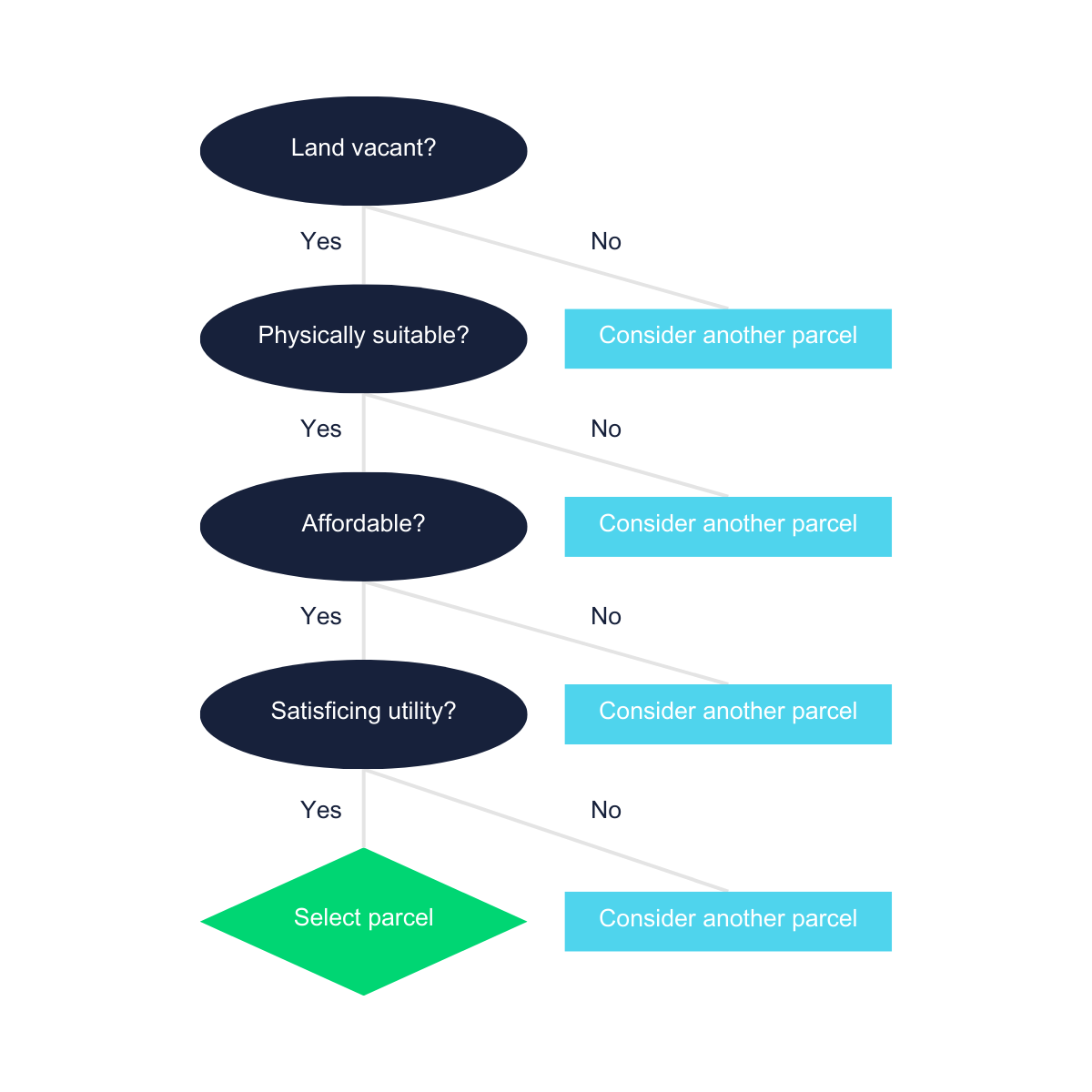

Indeed, one of the key parameters is “development control”, which accounts for the role of government in enforcing development regulations. This can be adjusted for local context. Other key model inputs include projected demand for housing, the socioeconomic profile of the city population, land prices and topography. In the model, households select land parcels to settle following a decision tree that considers the vacancy, physical suitability, affordability and utility of candidate parcels.

Figure 1: TI-City agents’ decisionmaking tree

The model computes the suitability of a given land parcel for each income group by taking into consideration the characteristics of the parcel – including land values, proximity to infrastructure and amenities, slope/elevation and land use zoning. The model accounts for how different income groups prioritise different location choice factors. The attractiveness of land parcels is dynamically updated during the prediction period based on the income profiles of neighbouring parcels.

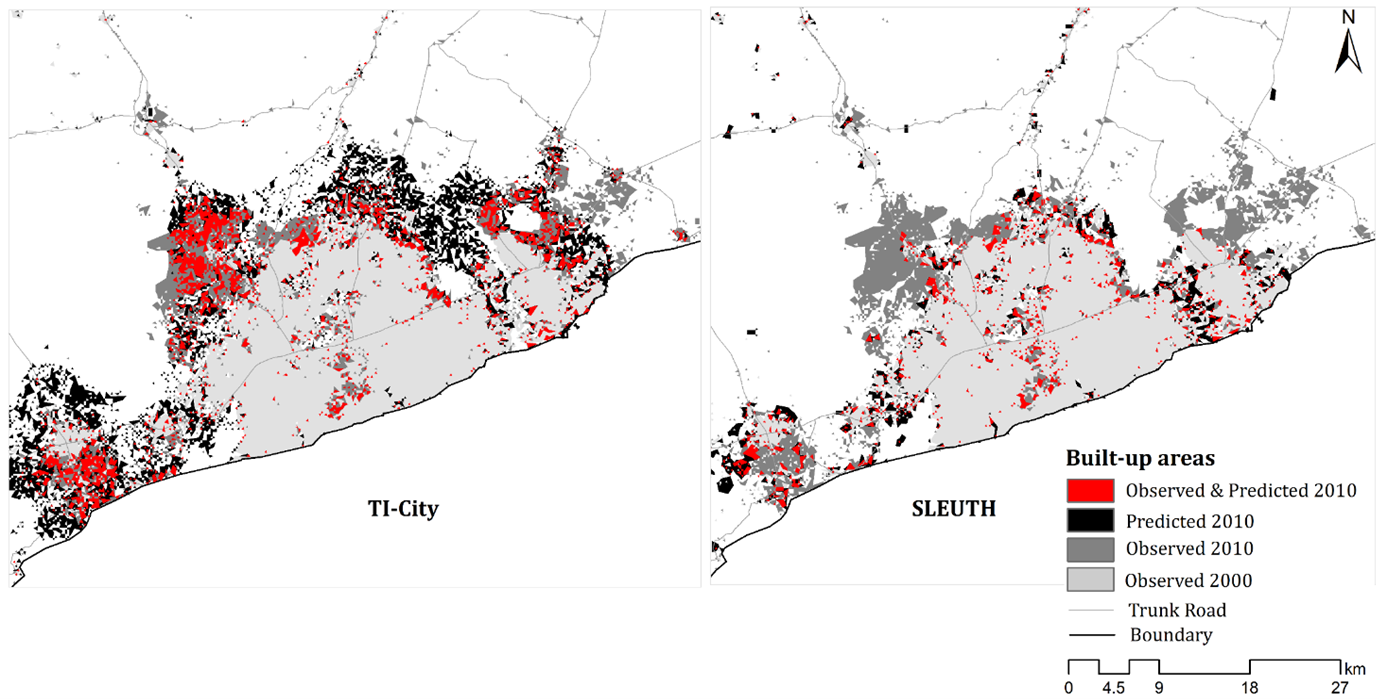

To evaluate TI-City, the model was applied in Accra and its performance was compared with that of SLEUTH. First, both models were used to predict the urban expansion of Accra from 2000 to 2010. The predictions from each model were visually and quantitatively compared with the observed (real) expansion of Accra. As can be seen in Figure 2, both models perform well in predicting inner-city developments. However, TI-City outperforms SLEUTH in predicting suburban developments. Quantitatively, TI-City explains up to 65% of the variations in urban expansion patterns of Accra, whiles SLEUTH only accounts for 27%.

Figure 2: Comparing TI-City predictions to SLEUTH in Accra

Impact: How TI-City informed the Accra structure plan

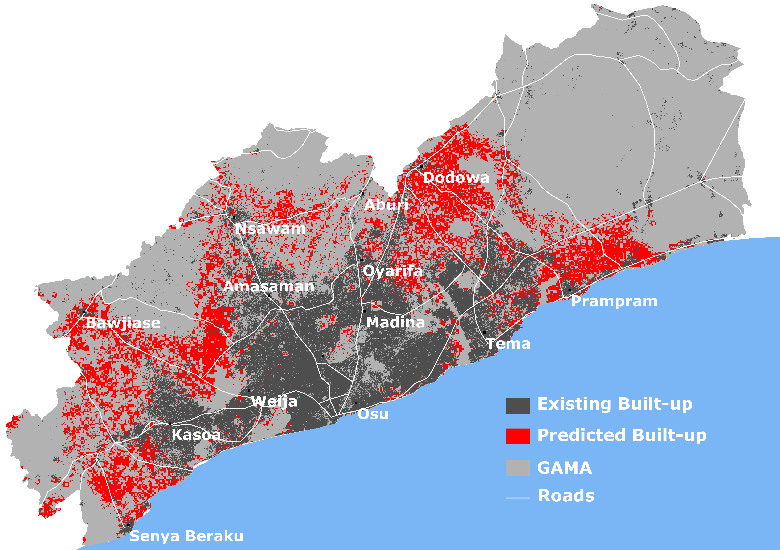

TI-City has been applied in the real world. Urban planners leading the preparation of a 15-year structure plan for the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA) have used TI-City to predict the urban footprint of the city in 2035. They have used the prediction from the model as a business-as-usual scenario to assess what will happen if there is no significant change in the development and implementation of land use regulations in the city.

For instance, using TI-City’s output, the planners have quantified there will be 18% loss of forest land, 12% loss of croplands thereby creating urban food insecurities, 4% loss of water cover and 18% loss of shrubs if the city continues to expand as usual. Following these predictions, the urban planners have developed alternative development scenarios, one of which is the “guided trend”.

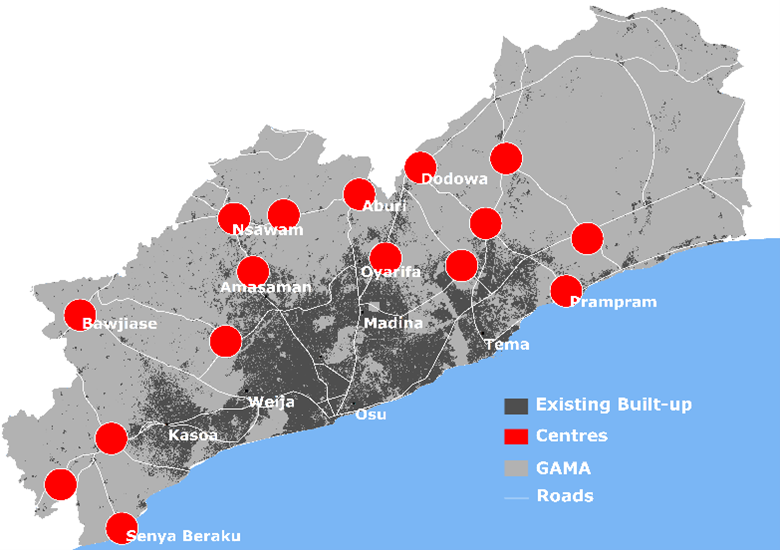

In the guided trend scenario, the planners recognise the predictions from TI-City as the most likely outcome. As this will be extremely difficult to change in the next 15 years, they attempt instead to guide the expected expansion into suburban centres, thereby minimising the negative impacts of the city’s expansion. One of the attempts by the planners to guide the city’s expansion is to locate and develop new centres in the suburban areas where the model predicts most of the expansion will occur as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3: Predicted expansion of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area, 2035

Figure 4: Guided trend scenario of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area

Source: The Greater Accra Metropolitan Area Structure Plan Draft Final Report by COWI

Applying TI-City to other African cities

The case of Accra demonstrates the potential impacts of using TI-City to predict urban expansion in other African cities. Currently, a three-year ESRC-funded project led by Felix Agyemang is looking into scaling up and applying the model to other African cities.

Conversations are underway with a number of cities that are members of the Africa-Europe Mayors’ Dialogue to gauge interest in applying this model. This is a live conversation and we would welcome hearing from other cities in Africa that would be interested in exploring this modelling technique.

Header photo credit: sercansamanci / Getty Images (via Canva Pro). Aerial view over Accra, Ghana.

Note: This article presents the views of the author featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.