By Teddy Kisembo (in-city urban development lead), and reflections from Ggaba action research team

Ggaba Market is located in Ggaba parish, in Makindye division, along the shoreline of Lake Victoria. The market hosts over 500 vendors purveying fresh and cooked food fish, non-farm merchandise shops and clinics. It faces flooding during the rainy season despite having a drainage system in place (spanning 571.5 metres).

Market vendors generate about 50 tons of waste per day, which, if left uncollected, poses health hazards for the community within the market and contaminates both the lake and underground water.

The Kampala action research project on inclusive markets and resilient communities in Ggaba Market seeks to tackle the interlinked issues of flooding, waste management and sanitation in urban markets.

The initial fieldwork that engaged the market community revealed a number of unexpected and nuanced realities. These surprises are reshaping the initiative’s approach and emphasising the need for contextualised and adaptive solutions.

The following were the main surprises and learnings from the ongoing exploratory study by the Ggaba action research team:

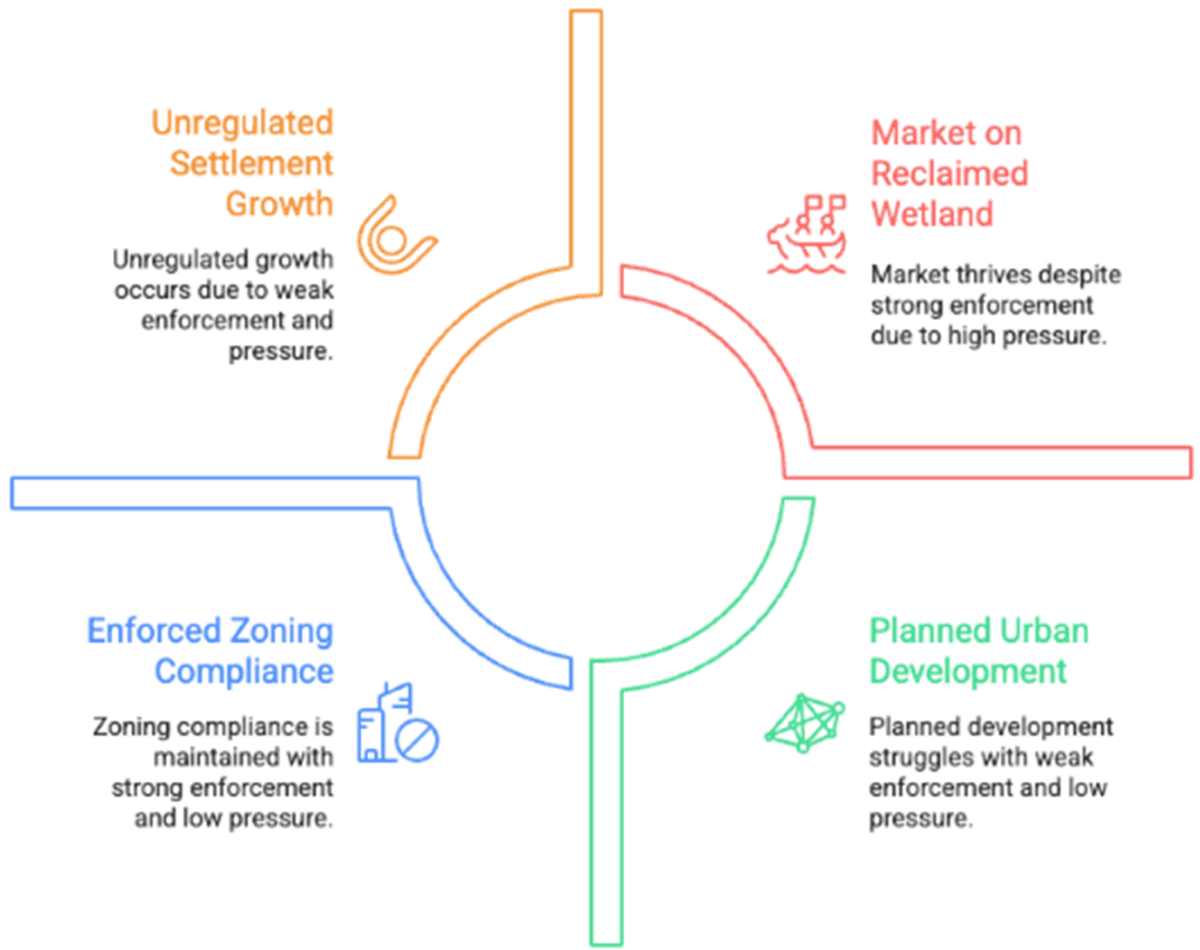

1. The land where the market currently stands is a reclaimed wetland, which historically served as a natural flood buffer for Lake Victoria. The market’s location within the lake’s buffer zone leads to questions around how settlements develop and grow, despite existing planning regulations. This highlights tensions between city plans and environmental regulations in Uganda and the realities of the informal economy and informal settlements, where pressures of the informal economy and the need for livelihoods often override city plans.

Urban planning and informal economy conflict

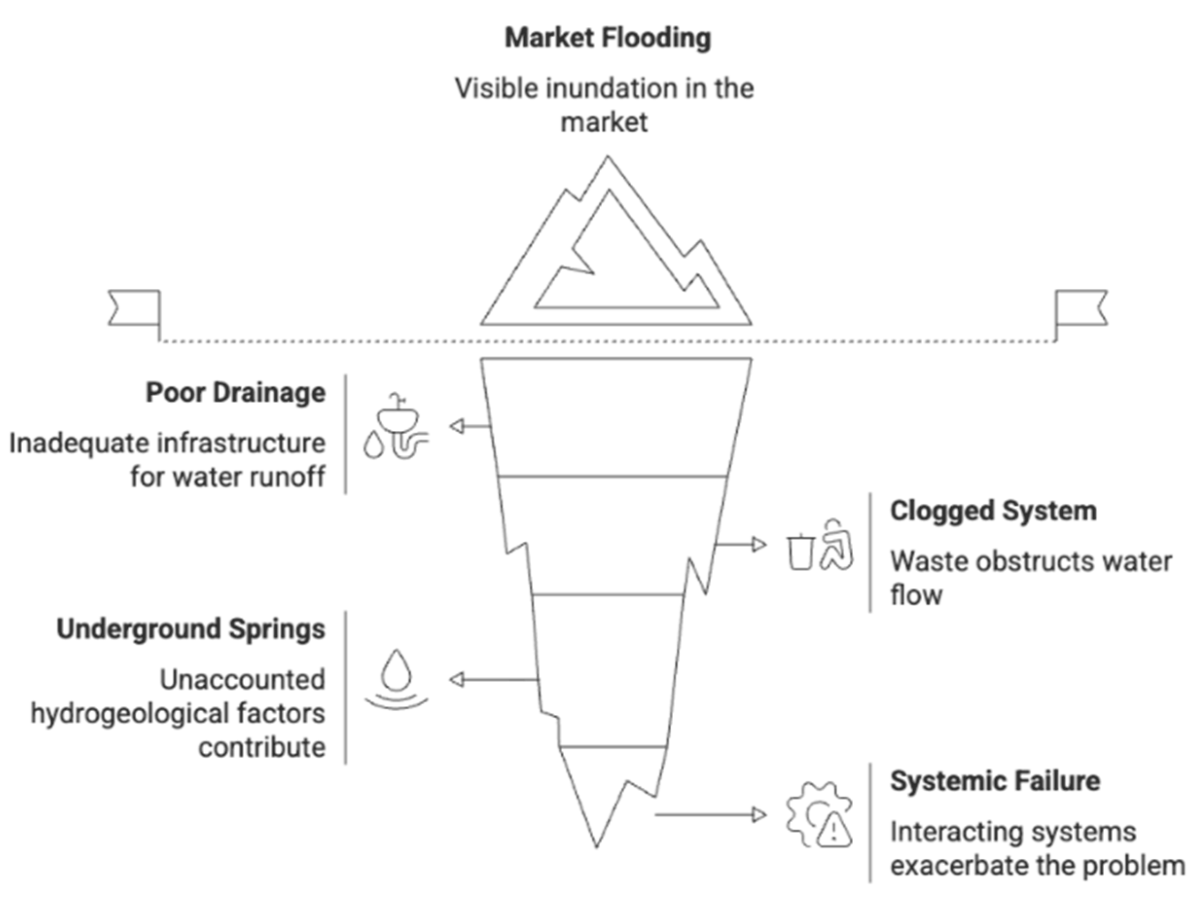

2. The presence of multiple underground springs compounds the complexity of the flooding challenge in Ggaba market. Its location at the lake shores and in a low-lying area leads to flooding, due to seasonal heavy rains and backflows of lake water, which are then amplified by poor and clogged drains.

The presence of underground springs adds an extra challenge for designing potential drainage solutions, as any effective intervention must consider the constant flow of underground spring water, so that standard infrastructure solutions may be insufficient. This surprise highlights the need for adaptive and context-specific infrastructure that takes into account the constant flow of underground spring water and lake backflows.

Underground spring

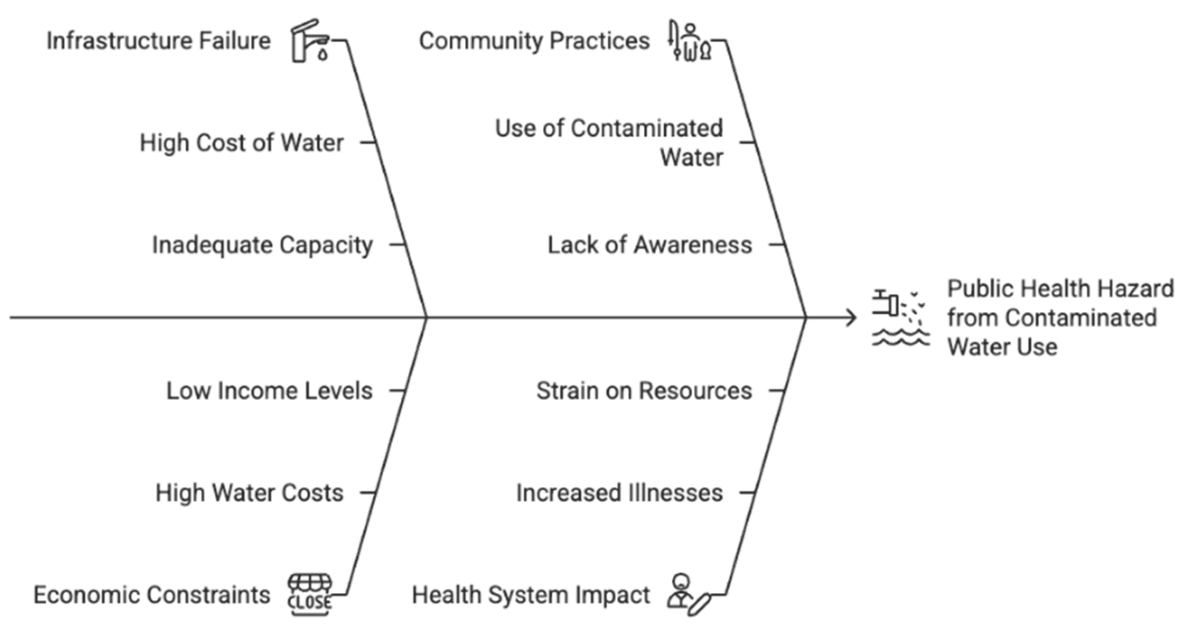

3. Market vendors directly use the unsafe lake water for various food preparation purposes. Despite being located near the National Water and Sewerage Corporation, Ggaba Market has no affordable safe water source for vendors. The practice of “okugatiriza wo amakyafu” – using unsafe water to complement the available safe water for food preparation and cleaning produce – is therefore widespread and poses a hygiene risk. The team also suspected that fish vendors use unsafe water to clean fish, which could be an additional health hazard. This is a direct consequence of the gap in provision of affordable safe water, forcing the market community to complement with a contaminated source.

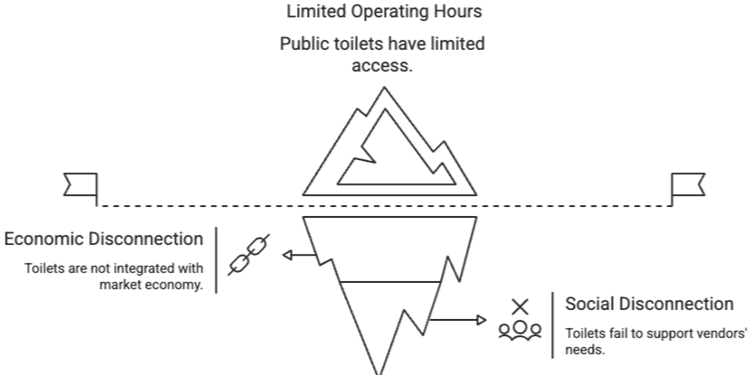

4. Public toilets at the market are not accessible at night. Public toilets are key sanitation facilities for the community – serving not only market vendors and customers, but also the wider catchment and residential area. While most toilets within the markets are accessible at a cost, their accessibility is a challenge. The operating hours (6:00am to around 10:00pm) do not accommodate the needs of vendors who often work until midnight. There is also increased demand for the facilities on days when events such as Friday prayers and market days take place. We also found that there are people who live in the market and need access to toilets. As a result, some have resorted to open defecation, dumping human waste in the garbage or in drainage channels or on top of houses.

A public toilet in the market

This mismatch between service hours and community needs shows a disconnect between the service providers (for the toilets) and the users, rendering a crucial facility inaccessible for many. This presented an ethnographic opportunity to better understand the evolving patterns of use as well as the social dynamics and negotiations that shape access to the public toilets.

5. Waste is dumped in the lake. Despite waste collection services being available in the market, some fishermen dump their waste directly into the lake, away from the shore. This prompted the team to further probe the efficiency of the current waste collection system and whether it leaves a gap that necessitates the observed behaviour. The usage of the lake as a waste dumping site poses both an ecological concern and stands as an example of both the creativity and the limits of systems in managing urban resilience, indicating an overwhelmed or inadequate formal waste management system.

6. Buyers’ preference for locally available fish, despite the poor state of the market environment, was a positive surprise. This helps vendors maintain strong demand and livelihoods, despite environmental challenges. It also provides a potential entry point for interventions into the resilience of the fish value chain and waste-to-resource innovations.

7. Proposal for developing Lake Victoria’s lakefront areas to ensure public access and restore shores. Being a lakeside market, Ggaba is likely to be affected by plans for lakeside development, as part of broader urban planning and infrastructure upgrades under the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area Urban Development Program. While proposals cite improved infrastructure and restored lake shores, Ggaba Market vendors face risks to their livelihoods if redevelopment displaces or disrupts their activities, posing broader social, economic and environmental challenges. This highlights interlinked dynamics where environmental restoration, governance decision and economic survival have to be balanced within inclusive urban development.

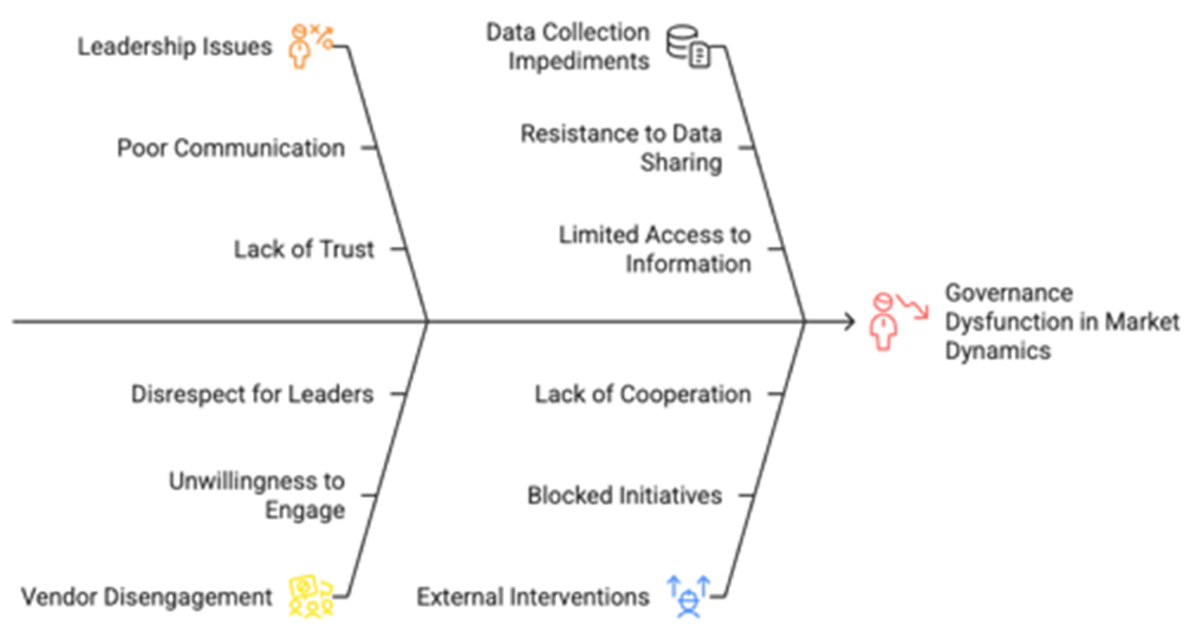

8. There is a visible disconnect between market vendors and market leadership, stemming from what vendors described as poor governance. This dysfunction made data collection difficult, as most vendors dislike and disrespect the market leaders, due to the poor leadership. The vendors were therefore largely unwilling to engage with the research team in the presence of certain leaders. However, they became markedly more forthcoming and participative once those leaders were no longer in the vicinity, indicating that internal governance is a primary obstacle to collective action and external interventions.

Clogged drainage channel

What do these surprises reveal about urban development issues?

The insights from this fieldwork reflect an interplay between environmental vulnerabilities, systemic gaps in urban services and community dynamics. These highlight critical connections and disconnections within urban development systems, revealing tensions between systems and the realities of informality. These surprises can be deeply understood through the ACRC conceptual framework, that allows an integrated analysis of the interplay between the underlying political settlement, interconnected city of systems and contested urban development domains that define Ggaba Market realities.

Examples of hybrid engagement do exist – for example, where KCCA provides intermittent services like waste collection twice a week and works with market leaders to profile vendors. This shows that KCCA is making efforts to negotiate with local leaders to maintain stability and deliver services, although significant improvements are needed.

The disconnect and mistrust between vendors and the market leadership draws attention to a fractured market-level power balance. This internal dysfunction hinders collective action and the success of interventions, as vendors are unwilling to engage when certain leaders are present.

Governance issues in Ggaba Market

Tackling compound challenges

The issues in Ggaba are not isolated, but are indicators of multiple, poorly integrated and failing systems, whose dysfunctional interactions create cascading hazards.

Flooding in the market is not just a result of the market’s location at the lake buffer and the backflow of the lake, but rather a failure of multiple systems interacting negatively. The drainage system is poor and clogged by a failing waste management system. The presence of underground springs introduces a hydrogeological reality for which the engineered systems are not designed, highlighting the need for adaptive infrastructure rather than standard solutions.

Market flooding is a systemic issue

The water system’s failure to provide affordable water has forced the community into a coping mechanism of using contaminated lake water for cleaning produce and utensils (“okugatiriza wo amakyafu”). This links the failure of an infrastructure system to acute risks within the food distribution and health systems, creating a public health hazard.

Public health hazard from water system failure

The public toilets, which are part of the sanitation system, cannot keep up with the pace of the market’s economy. Their limited operating hours exclude vendors who work late, demonstrating a system that is not integrated with the social and economic systems it is meant to support.

Disconnected public toilets undermine market economy

Mapping lessons across domains

The surprises from Ggaba Market play out across several overlapping urban development domains:

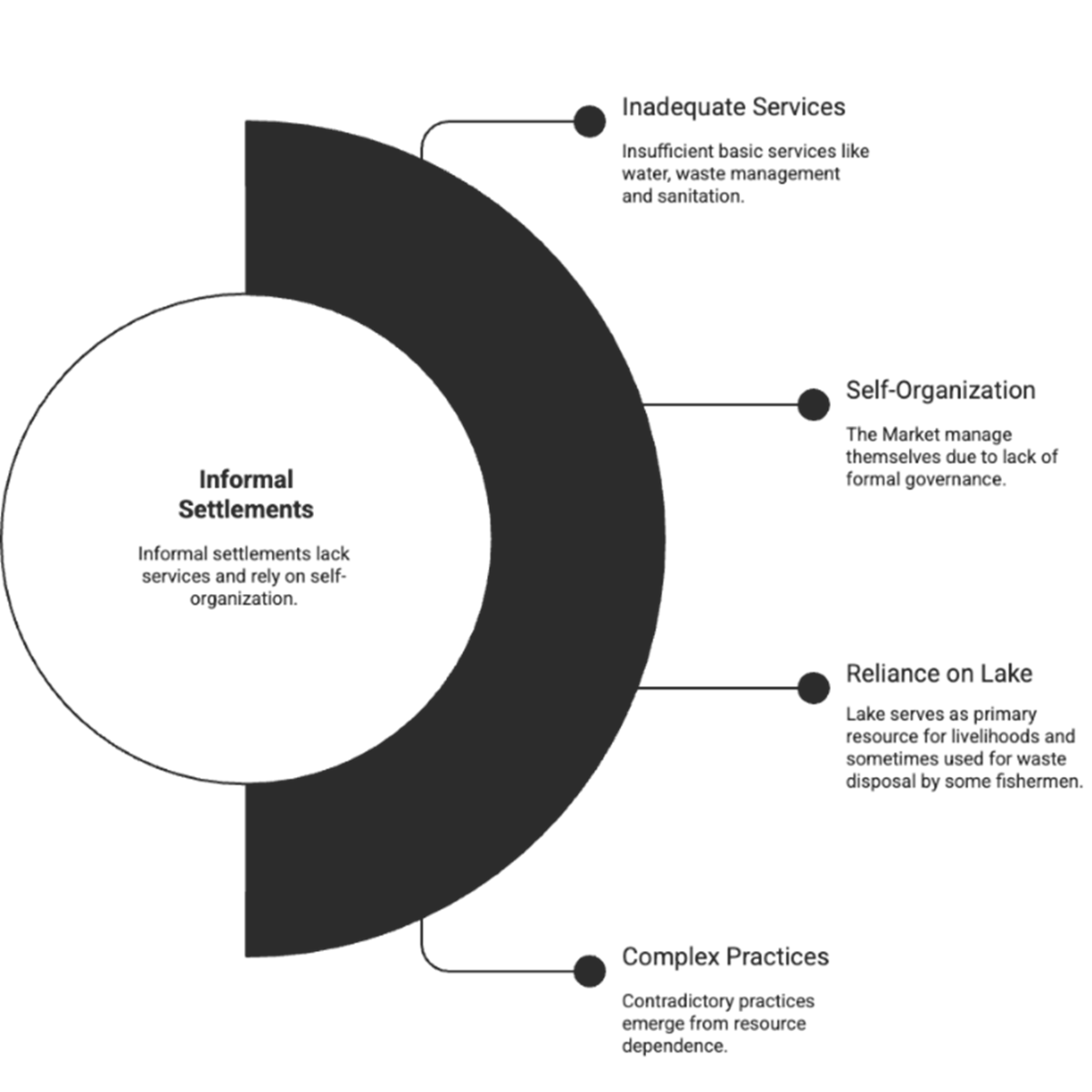

> In the context of the informal settlements domain, the market is characterised by inadequate services and self-organisation. The reliance on the lake for both livelihoods (fishing) and waste disposal demonstrates the complex and often contradictory practices that emerge in this domain.

The complex dynamics of informal settlements

> The use of unsafe water places the market’s activities within the health, wellbeing and nutrition domain. Any intervention aimed at improving livelihoods must also address the health risks embedded in daily practices, requiring the integration of public health, water and food safety solutions.

> The proposed waterfront development pushes the market into the land and connectivity domain. The plan introduces city and national-level actors, whose vision for a modernised waterfront may conflict with the existing market. This highlights the need for proactive engagement to ensure the market community is not excluded from future development.

Reframing the initial fieldwork surprises through the ACRC framework helps create a more profound understanding of the issues facing Ggaba Market. These are not simply technical problems, but are embedded in the political settlement, the fragmented nature of service delivery systems and contested domains of urban development. This is key for developing the political and systemic interventions necessary for building market resilience.

Photo credits: Ggaba action research team

Note: This article presents the views of the authors featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.