Urban transformations: Aid, trust and ACRC

This is the third in a series of blog posts focusing on how urban reform happens and where ACRC fits into change processes. The first blog post focuses on how ACRC’s approach links to issue-based programming, the second explores urban transformation and the centrality of trust in politically engaged development programmes, the third takes a closer look at how ACRC adds value to urban reform, and this fourth one highlights how ACRC is helping build community capabilities to address urban challenges.

By Diana Mitlin

For many development programmes, building capabilities and capacities means training, or teaching groups about specific skills or issues. For ACRC, we aim to build the capabilities of communities through the action research process. This is a process that SDI (and other organisations) use widely – but is worth unpacking.

Before we do, it is useful to highlight the difference between capacity and capability:

Capability refers to the ability of the individual or agency to do a specific task. Are they able to do it? Do they understand what is required, and do they have the skills and experience necessary to move forward successfully?

Capacity refers to the scale of the ability to respond to the change.

This blog focuses mainly on capability, which is frequently confused with capacity.

For example, state agencies and individuals may have the capacity (such as time and resources) to respond, but they may lack the capability (specific skills) to do so. Equally, they may have the capability to act, but simply not have the resource available.

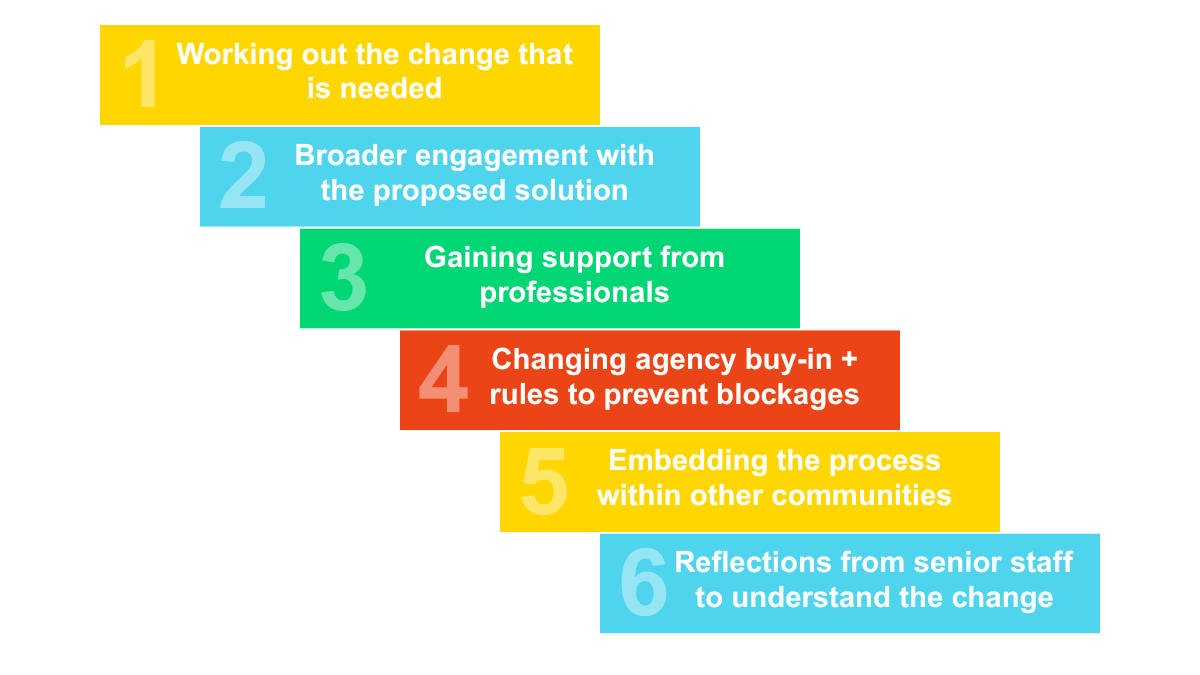

I’m going to outline six stages of building community capabilities, through the lens of an action research project we’ve been supporting in Maiduguri, northeast Nigeria. The project has built on an existing effort by the Borno State Geographic Information System (BOGIS), which aims to better integrate informal settlement residents into land titling processes.

Complexities around land tenure and ownership in Maiduguri have led to frequent contestation and evictions, with lowest-income groups the most vulnerable. The project set out to unearth ways to tackle uncertainties around customary land tenure processes and advance the interests of disadvantaged groups.

1. Working out the change that is needed

The first stage requires identifying groups deeply embedded in relevant processes who are innovators. We provide them with space to analyse the problems and identify possible solutions. Those solutions are then discussed with a wider group of stakeholders. Once the proposed solution is crafted, reviewed and is thought to work, then the process of capability development moves forward.

In Maiduguri, the academics preparing the action research project were keen to build in the customary leaders from the beginning, as they understood the problem. The confusion when formal, state processes landed in the low-income neighbourhood was evident to them. Hence, they wanted to address this challenge by introducing an individual able to mediate between the state agency and community members. They proposed a solution that made sense to the academics.

2. Broader engagement with the proposed solution

For community members, testing the idea and realising the success of ideas that emerge at this first stage help to derisk the process of using innovations. Users need to understand and be confident about the processes being introduced. Equally, this stage offers a further check. If people are not convinced by the idea when it is implemented in practice, there may be a need for a rethink and a redesign.

For processes that are uncomfortable for state agencies, this stage of broader adoption within a neighbourhood helps to generate a critical mass of people who want to see the change happen, which boosts the chances of it being officially adopted. Without upward pressure from the community towards state officials, adoption is unlikely.

For Maiduguri, the solution was a community volunteer for each neighbourhood (who could claim a stipend, to keep costs low). This was someone able to navigate the complexities of BOGIS and address their needs but not be thrown if the questions were hostile or ambivalent. It was also someone who would engage with the people who wanted titles and who was trusted to act in their interests. The character of the individual matters a lot.

3. Gaining support from professionals

In the intense world of urban informality (both spatial and economic), there is every likelihood that the change will involve professionals. These might well be officials (at multiple levels of the state, including street-level bureaucrats and their managers) and/or NGO workers. The change is likely to require them to do things differently. They need to understand the changes needed and why they are required to make them.

This capability development is also part of the testing process. We may discover that the new processes interrupt existing plans and programmes. The first phase of capability development also enables us to understand which language has to change to communicate effectively.

In Maiduguri, this meant co-developing the form with the officials responsible for registering the applications and undertaking the GIS mapping in BOGIS. They needed to buy into this modification to the process, and to sign off on the functionality of the remunerated volunteer. Fortunately, they were positive from the beginning.

BOGIS explained that one of the main obstacles that they faced was the need to link up to individual would-be titled landowners and agree times for the GIS mapping. Sometimes a time was agreed but the individual was not at home. Individual applicants could be a considerable distance from each other, increasing their travel time.

BOGIS officials suggest it would be more efficient to deal with the group of applicants from the same neighbourhood, given that they had a reliable contact person. The ease of doing their job would improve significantly if they did not have the additional costs associated with individual applicants.

4. Changing agency buy-in and rules to prevent blockages

Capability development will also be required from those who control the agencies whose behaviours we are trying to change. They need to understand the process and how it addresses existing blockages within their agency. This may involve new capabilities and new capacities if the change makes the agency much more effective in its work.

As in Maiduguri, once the street-level bureaucrats have bought into the process, there is a need to ensure that those higher up in the organisation appreciate the changes and their functionality. Otherwise there is a risk that senior managers may block the process. For example, they might point out that the remunerated volunteer has no authority from BOGIS. They are also needed, potentially, at the next step when the individual becomes a permanent feature of the BOGIS process. And it may be that some individuals in the agency are reluctant to countenance reform (perhaps because they have found ways to benefit personally from the previous process). Fortunately, the executive secretary of BOGIS is actively involved and engaged in the detail of the process. He also understands the advantages of this new process.

5. Embedding the process within other communities

We cannot assume that the benefits of the new process will be immediately obvious to either the state agency or community members. Hence, there may be a need for outreach programmes that explain the benefits of the new process to others and provide succinct information to enable them to take up what is on offer. The information and examples of what has happened elsewhere may be enough to enable them to take up the new process – but training programmes may also be required. Those training programmes are most likely to be successful if the experience of taking up the new programme is integrated into the training.

This is where we are currently at in Maiduguri. The innovation of the community volunteer, together with the redesign of the application process, is critical to the success of our project and remains at the level of the project, which will continue for a further few months. We don’t know what will happen then. It might be that BOGIS is convinced that this new hybrid informal-formal system is just what they need to ensure that more of those living in informal neighbourhoods secure titles, and that this stipend is a legitimate cost to add to their expenditure. If other neighbourhoods – not included in the action research project but waiting and observing – are keen, then this may sway BOGIS and help to secure their support.

6. Reflections from senior staff to understand the essence of the change

Finally – and significantly – there is a need to build the capability of more senior staff and political leaders, who can usefully reflect on the underlying drivers behind the intervention and the associated innovations, and on how the process has changed. This may also include those inside and outside the state, at neighbourhood to city scale.

This is also capability development, but more focused on the strategy and rationale, rather than the steps within the process itself. It is essential for those senior staff to appreciate the process involved, and the value that it brings. It will enhance the ability of the senior staff to realise the significance of the change and enable them to follow up (through appropriately designed feedback loops). It may also trigger other processes that are consistent with these principles.

In Maiduguri, it is the ability to blend formal and informal processes to support land titles that is making the difference. Such hybrid service delivery may be helpful in other urban systems. Communication about capabilities and capacities can usefully be shared once the process has demonstrated its value and the reports have been completed.

Diverse leaders have already been involved in supporting the equitable land titling project, including senior staff in both the governor’s office and the administration of the Shehu, head of Borno’s traditional institution. The executive secretary of BOGIS is already involved in the project and is well placed to share this knowledge. Grassroots leaders may also be significant in terms of lesson learning. They can share their observations and encourage new approaches in other services that they want to expand to reach new populations.

The importance of capability development to address urban challenges

With one in seven of the global population living in urban informal neighbourhoods, local research and development to produce a range of solutions to systemic urban challenges is urgent. As illustrated here, a few carefully designed activities can make a substantive difference – and there are many such innovations. But they need to be introduced, tested, refined and shared.

Capability development is a process that goes well beyond training programmes in the classroom. Engaged and focused learning in real time appears to make the real difference. In the urban context, dense with people and social institutions, a multi-scalar approach is essential – drawing in key players in diverse contexts to establish self-reinforcing learning cycles.

Read more about:

> The land titling project in Maiduguri

> The Maiduguri city research report

Header photo credit: aroundtheworld.photography / iStock. Aerial shot of the informal settlement of Kibera in Nairobi, Kenya.

Note: This article presents the views of the authors featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.