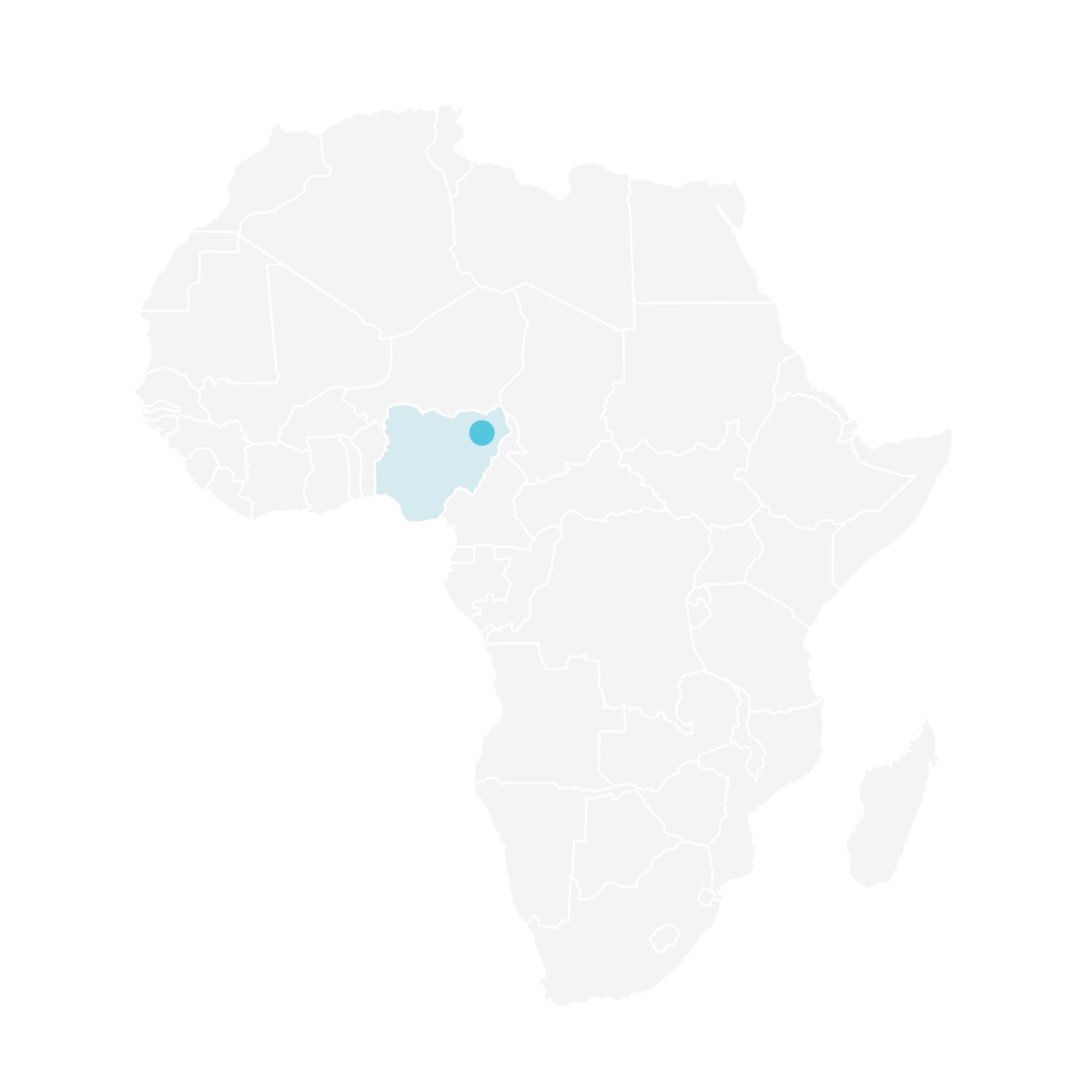

Maiduguri

Maiduguri is the largest city in northeast Nigeria and the capital of Borno State.

Nigeria’s Borno State has been severely affected by the Boko Haram insurgency and the resulting insecurity has led to economic stagnation in Maiduguri, with the city bearing the largest burden of support to those displaced by the conflict.

A population influx of more than 800,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) at the peak of the crisis exacerbated vulnerabilities that existed in the city previously, including weak capacities of local governments, poor service provision and high youth unemployment. As of November 2020, approximately 300,000 IDPs still reside in Maiduguri.

Maiduguri: City Scoping Study

Read the full study below, or download it as a PDF here.

Read now

African Cities Research Consortium

Maiduguri: City Scoping Study

By Marissa Bell and Katja Starc Card (IRC)

Maiduguri is the largest city in north east Nigeria and the capital of Borno State, which suffers from endemic poverty, and capacity and legitimacy gaps in terms of its governance. The state has been severely affected by the Boko Haram insurgency and the resulting insecurity has led to economic stagnation in Maiduguri. The city has borne the largest burden of support to those displaced by the conflict. The population influx has exacerbated vulnerabilities that existed in the city before the security and displacement crisis, including weak capacities of local governments, poor service provision and high youth unemployment. The Boko Haram insurgency appears to be attempting to fill this gap in governance and service delivery. By exploiting high levels of youth unemployment, Boko Haram is strengthening its grip around Maiduguri and perpetuating instability.

Maiduguri also faces severe environmental challenges, as it is located in the Lake Chad region, where the effects of climate change are increasingly manifesting through drought and desertification. Limited access to water and poor water quality is a serious issue in Maiduguri’s vulnerable neighbourhoods. A paucity of drains and clogging leads to annual flooding in the wet season. As the population of Maiduguri has grown, many poor households have been forced to take housing in flood-prone areas along drainages, due to increased rent prices in other parts of the city.

Urban context

Maiduguri is the oldest town in north eastern Nigeria and has long served as a commercial centre with links to Niger, Cameroon and Chad and to nomadic communities in the Sahara. Almost all languages and cultural groups from across Nigeria and neighbouring countries can be found in Maiduguri.

The city was selected in 1907 by the British to be the capital of the Borno Emirate, which was the surviving traditional ruling structure after the end of the Kanem Borno Empire (1380-1893). Maiduguri functioned as the divisional and provincial headquarters of Borno Native Authority and Borno Province, respectively, during the colonial administration. After Nigeria proclaimed independence from British rule in 1960, Maiduguri became the capital of North Eastern state in 1967 and that of Borno State since 1976.[1]

Maiduguri city has grown over the years in line with Nigeria’s general urbanisation trends, primarily driven by rural-to-urban migration. The last reliable demographic data from the 2006 census estimates the population to be 748,123 (Jere and MMC LGAs), which means Maiduguri is categorised as a “medium” size city in the Nigerian urban system.[2] Maiduguri is composed of two local government areas (LGAs), namely: Maiduguri metropolitan council (MMC) and Jere LGA, with some sources including Konduga and Mafa LGAs into “greater Maiduguri”. These areas combine to cover a total land area of 543 km2.[3]

Over the past two decades, Borno State “has suffered growing security, capacity and legitimacy gaps, demonstrated in the declining capacity of its institutions to deliver public goods, including security, transportation, water, medical care, power and education”.[4] Since 2009, 2.1 million people have been displaced in Borno State, due to threats from Boko Haram, with hundreds of thousands seeking refuge in Maiduguri and in the camps surrounding the city. The city of Maiduguri has borne the largest burden of support to those displaced by the conflict, housing over 800,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) at the peak of the crisis, with more than 88% residing outside of camps.[5] According to a 2016 UNOCHA statement, greater Maiduguri saw its population increase from 1 million to 2 million with the influx of people displaced from other areas of the state. An estimated 10-50% of IDPs were projected to stay in the city.

As of November 2020, approximately 300,000 IDPs still reside in Maiduguri.[6] This influx exacerbated vulnerabilities that existed in the city, even before the crisis, including weak capacities of local governments, poor service provision and high youth unemployment. The exact population is unclear, but the combination of natural population growth since 2006 and the displaced population likely places Maiduguri among larger cities in Nigeria, of between 1 and 5 million inhabitants.

The existing population had largely outgrown the urban plans of the city before the crisis. A spatial study of the city found that unused land decreased by 21.8% from 2002 to 2012.[7]

The displacement crisis in Maiduguri occurred within the context of a weakened national economy, entering into a recession due to declining oil prices in 2016 and slightly recovering since 2017. Even before the crisis, Borno State was one of the most impoverished states in Nigeria; as of 2010, it had the second highest absolute poverty rate of 68%.[8]

Nigeria’s prolonged period of economic growth prior to 2016 did not decrease poverty in the north east, as it did not lead to the diversification of the sources of income for poor households, who continue to engage in low-productivity, subsistence activities.[9] The local economy has traditionally been rooted in farming and fishing, along with a small manufacturing sector.[10] Sustainable employment opportunities in Maiduguri are limited. Some of the largest companies, such as Maiduguri Flour Mills, shut down during the peak of the insurgency in 2013 and despite reopening, following security improvements since 2015,[11] are still only producing at a limited rate. Small and micro businesses dominate the economy in Maiduguri. National policy aims to support the growth of micro, small and medium businesses to promote growth and decrease chronic unemployment, but “there is simply not enough industry and employment in the city to absorb so much excess labor”.[12] As a result of limited productivity, the state is heavily dependent on revenue from the federal government.[13] With the onset of the recession, federal funding has been cut, which severely affected Maiduguri and Borno State, including the few local industry employers. This further exacerbated the already high pre-crisis levels of unemployment amongst a growing youth population and may have pushed them towards joining the Boko Haram and other religious insurgents.

Maiduguri lies on relatively flat terrain, which is part of the vast undulating plain sloping towards Lake Chad. In the Lake Chad region, traditional surface water sources are shrinking very fast and the effects of climate change are being increasingly felt, manifesting itself through drought, desertification, and overall environmental degradation.[14] According to UNEP, inefficient damming and irrigation methods in the countries bordering the lake are also partly responsible for its shrinkage. The combination of climatic variability and poor water governance has threatened the ecological and socio-economic integrity of the Lake Chad region.[15] As a result, water supply is scarce in Borno State, and demand has increased in Maiduguri with the influx of IDPs. Water shortage is also a driver of displacement; people who arrived in Maiduguri during the recent displacement crisis, which started in 2014, most often left rural areas because of armed conflict or a combination of conflict and drought. [16]

Political context

Nigeria is a federated country with three tiers of government: federal, state and local government areas (LGAs). Governors are elected at the state level and serve as the chief executives of their states as well as the chief security and law officer. As of March 2021, the governor of Borno is Babagana Umara Zulum and he is generally considered a popular reformer and man of the people. He serves under the platform of the All Progressive Congress, the federal ruling party, and holds significant power and influence. The governor has control over all statutory budget allocations, including those to all 27 LGAs within the state. This gives the position of state governor substantial decision-making authority. The majority of the state’s budget comes from allocations from the national government’s Federation Account.

In late 2020, the first elections in 13 years were held for LGA officials (chairmen and ward councillors) in Borno State. In the caretaker period prior to elections, the LGAs were chaired by unelected officials who were appointed by the governor and frequently rotated. The State House of Assembly does not play a major role in policymaking.

Additionally, while not part of the federal government structure, traditional leaders play an important role in communal affairs. Within Borno State, there are seven emirates, each headed by a shehu. The shehu is appointed by the governor and presides over an emirate council with four tiers of authority: shehu (state), aja/hakimi (district), lawan (ward), and bulama (neighbourhood). The shehu plays a key role in Maiduguri in terms of community mobilisation, dispute resolution, citizen securityand information dissemination.[17] Bulamas/lawans are often considered the most influential individuals within communities. Political actors are very deferential to the ajas and other higher-level traditional leaders.

Historically, LGAs in Borno State have been considered weak and under-resourced. According to law, LGAs, including the Maiduguri LGA, are responsible for sanitation, markets and parks, naming of streets, recreation centres, open spaces, slaughterhouses, control of street advertisements and use of public addresses. LGAs also share responsibility with the state government for the provision of primary healthcare facilities, basic education, agricultural and animal health extension services, provision of roads, streetlights and control of water pollution. In addition, each LGA is allowed to collect local taxes from businesses but tax revenue tends to be a small portion of their budget.

Urban challenges

The original Maiduguri master plan was prepared in 1976. The Borno State urban planning and development board has been responsible for urban planning in Borno State since then,[18] undertaking sector-level strategies and urban renewal of existing structures. The 1976 masterplan established a set of public spaces throughout Maiduguri. However, since then, many public spaces have been built upon either by private businesses or for government buildings. Some public spaces, such as schools or unused spaces in the city, have been occupied by IDPs as informal shelter. The availability of public spaces differs by community but there does not appear to be any systematic discrimination in terms of availability or access of a public space. The state board’s planning approach has been to expand the city outwards and reduce the density in the centre. In line with the original masterplan, the city has designated areas for urban agriculture, especially in Jere, including opportunities for crop cultivation, market gardening and animal rearing.

In May 2020, the governor of Borno State unveiled a new Master Plan to expand Maiduguri.[19] As of February 2021, there is a demolition campaign ongoing in Maiduguri. The government has identified for demolition 1,300 houses in floods zones in central areas of Maiduguri. The rapid growth and development of Maiduguri has led to land use changes affecting hydrological regimes and resulting in frequent flooding. The situation is further exacerbated by the lack of drainage channels and the dumping of waste into existing ones.[20]

In November 2020, the governor launched the Borno State Development Plan, a 25-year long-term post-conflict reconstruction and development plan to drive stability and stimulate growth.[21] The viability of the plan and its impact on Maiduguri remain to be seen.

Economic challenges

The insecurity in north east Nigeria has led to economic stagnation in Maiduguri. Transport and trade restrictions and inaccessible areas around Lake Chad have impeded economic activity in Maiduguri. The insurgency and road insecurity have affected the flow of people, goods and raw materials in the area. Movements and economic activity were further restricted due to counter-insurgency operations. Security in Maiduguri and the surrounding areas temporarily improved in 2016, which offered some respite to businesses in the city, but the area remains unstable. Goods are transported and people move around the region at great risk to their safety. As of 2021, there are also several roads to smaller towns in Borno that are blocked by the military, greatly restricting economic flows.

New economic activity has emerged due to the displacement crisis, with local markets growing around IDP camps. The presence of international humanitarian actors has increased demand for day labour in construction, transport and the procurement of supplies in Maiduguri. The demand for rental houses, apartments and services has also increased, due primarily to the surge in humanitarian workers and some IDPs capable of renting, which in turn increased house rent prices.

The economy in Maiduguri remains characterised by a high rate of unemployment, particularly among young people. The influx of IDPs has strained the mainly informal labour market in Maiduguri. The labour market was further affected by the collapse of large-scale industries. Pre-crisis, the host population primarily worked as traders, whereas most of the IDPs from LGAs outside of Maiduguri primarily depended on subsistence agriculture and livestock trading. While there are no official statistics or labour market assessments, most estimate that the vast majority of young people are unemployed. The IRC 2016 Urban Context Analysis indicated that youth unemployment is one of the biggest issues facing Maiduguri. Many are out of school and tend to “roam”.[22] While it is unclear whether unemployment was a main driver of recruitment to Boko Haram, many young people that joined Boko Haram reported accepting “loans prior to joining or joined with the hope of receiving loans or direct support to their businesses”.[23] The lack of economic opportunities or alternative opportunities for starting a business without powerful “godfathers” to support them, seems likely to have driven some young people towards participating in this violent movement.

Social challenges

Over 80% of IDPs in Maiduguri live within host communities. Many IDPs share religious, cultural, family and ethnic ties with the host community. Combined with a culture of generosity and encouragement from religious institutions for people to support IDPs, this has led to many wealthy people allowing IDPs to settle on their property, and other host community households to open their doors, often housing more than 20 individuals in a single household. Social cohesion in the urban communities appears to be strong. Long-term displacement appears to have led to a degree of trade and economic integration between host and displaced communities. However, there is also some mistrust towards IDPs, due to their perceived association to the insurgency.

From the host community perspective, there is recognition that there has been an increase in investment and support to Maiduguri due to the Boko Haram insurgency and the IDPs crisis, such as the construction of new boreholes and provision of school uniforms for pupils. But the host communities also see IDPs receiving preferential support, while they too are in need. While the situation is relatively stable, there is recognition amongst the host community that tensions could rise and some note an increase in petty crime.

Political challenges

Boko Haram grew out of a radical Islamist youth group in the 1990s in Maiduguri and was officially founded by Mohammed Yusuf in 2002. The group’s activities first turned violent in 2006, with riots in Maiduguri. By 2009, the group held extensive territory, particularly in Borno State. Maiduguri city experienced over 100 low-level attacks and several major events, including 2009 attacks killing 75 people and bomb attacks in 2015 resulting in 20 casualties.[24] In 2021, Boko Haram and splinter group, Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), continue to threaten and attack cities and communities. In some communities, ISWAP/Boko Haram have gained increased acceptance by addressing a gap in governance and service delivery. Boko Haram is an ongoing challenge to peace and security within the city and surrounding areas.

In response to the ongoing Boko Haram threat, the Nigerian military resorted to the so-called “super camp strategy”, consolidating their presence in stronger and better equipped camps in rural areas. While this approach has reportedly improved the ability of the military to counter the insurgency, it has eroded the protection of civilians in contested areas and exposed them to insurgent exploitation.[25] To fill the security gap, the Nigerian military and state officials rely heavily on militias and vigilante groups operating under the umbrella organisation, Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF). In many communities, CJTF are key providers of policing and security, as well as governance functions, including dispute resolution and judicial processes. In Maiduguri, too, their responsibility goes beyond protection against terrorism to standard roles of community policing, such as stopping crimes or resolving violent disputes. When bigger issues arise, they will refer them to the federal police. CJTF has its own representatives at the LGA and state level. However, the reliance on CJTF is increasingly problematic. As they assume a wide range of governance powers, CJTF are an increasing challenge to the authority of local government officials and traditional leaders. Reportedly, they have become integrated in the north east’s war economy, profiting from instability and conflict.[26]

Environmental challenges

Limited access to water is a main issue in Maiduguri’s vulnerable neighbourhoods. The central system for the supply of water is limited. The majority of homes in Maiduguri are dependent on boreholes or purchasing water. The installation of water pumps has not kept pace with the increased population. Many of the existing water points are non-functioning and the water is of poor quality, due to shallow drilling of boreholes. Communities are also served by water vendors but the price is cost prohibitive for many.

The main natural hazards facing Maiduguri are drought and floods.[27] Droughts typically occur approximately every ten years in Maiduguri and last from one to six years. Droughts most adversely affect poor households, by lowering the availability and increasing the price of food. It also impacts households dependent on urban agriculture for their livelihoods.

Flooding has affected the majority of residents in Maiduguri. As the population of Maiduguri has grown, many poor households have been driven to take housing in flood-prone areas along drainages. Floods cause pit latrines to fill up and spill, polluting the area and increasing the incidence of water-borne diseases, such as cholera and malaria.

Sanitation is jointly supported by local government councils and the State Environmental Protection Agency. Lack of proper sanitation and waste disposal is a pressing problem.

Political factors shaping how urban challenges are addressed

There is limited planning occurring at the LGA level. LGAs have responsibility for preparing local plans and budgets on an annual basis that are submitted to state level and then receive budget allocations. The majority of annual budget allocations cover personnel costs rather than service delivery. Planning primarily occurs at state level and is controlled by the Ministry of Local Government and Emirate Affairs.

The dominant ethnic group in Maiduguri is Kanuri, who are typically of Islamic faith. The leadership of Boko Haram were Kanuri, though group members come from a range of ethnicities. They include Hausa, Shuwa Arab, Babur Bura, Fulani, the Gwoza and Marghi.[28] In addition, the city has many minority ethnic groups, including Igbo, Ijaw and Yoruba – many of whom are Christians. Ethnic politics in Nigeria is a complex subject, due to the role ethnic identities play during elections.

Parts of the city have historically been dominated by a particular ethnic group, which is reflected in the area names (for example. Hausari for Hausa, Shuwari for the Shuwa Arabs, Fulatari for Fulani, Gwozari for the Gwoza people).[29] As the city began to grow and become much more commercialised, it became more complicated to distinguish areas within the city exclusively by ethnicity. Therefore, the city is now a mix of homogeneous and multi-ethnic areas.

Religion is a complex issue in Maiduguri. There are no official statistics, but key informants estimate that up to 25% of the Maiduguri population is Christian, with the remaining majority being Muslim. While Christians were initially the primary target for Boko Haram, the terrorist attacks quickly spread to Muslim groups in the city. It is hard to fully disentangle religious identity from that of ethnic and political identities. Similar to ethnicity, social networks and patronage influence how resources are shared and divided in the community.

According to Global Gender Gap 2016 report, Nigeria ranks in the bottom 20% of countries (114) in terms of gender equality. The report found more equality around economic participation but significant inequality in terms of health and survival, educational attainment and political participation. A 2016 report on Masculinities, Conflict and Violence[30] that included sampling from Maiduguri city, found there are strongly entrenched notions of the role of men and women in society, according to which women are expected to be submissive and devote themselves to their family. There are only a very limited number of formal leadership positions for women in Maiduguri. Within the traditional authority structure, the shehu recently created two positions specifically for women on the Emirate council but otherwise, the hierarchical structure has no place for women. Women instead form their own groups at the local level and have women leaders who attempt to influence decisionmakers.

Maiduguri faces multiple, complex and inter-related challenges from issues such as service delivery, climate change, violent extremism from external armed groups, urban displacement and implementing governance reforms. The ACRC consortium is well placed to bring together city and local officials, academics, humanitarian and development actors working to address these issues to generate evidence and practical sustainable, resilient solutions for Maiduguri and cities similarly affected by the compounding effects of conflict, climate change and weak governance.

References

Bloch R., Fox S., Monroy J. and Ojo A. (2015). Urbanisation and Urban Expansion in Nigeria. Urbanisation Research Nigeria (URN) Research Report. London: ICF International.

Felbab-Brown, V. (2020). “As conflict intensifies in Nigeria’s North East, so too does a reliance on troubled militias”. Order from Chaos blog, 21 April. Brookings. Available online (accessed 11 May 2021).

Fortnam, M. P. and Oguntola, J. A. (eds.) (2004). Lake Chad Basin, GIWA Regional Assessment 43. University of Kalmar, Kalmar, Sweden/UNEP.

IDMC (2018). “City of challenge and opportunity Employment and livelihoods for internally displaced people in Maiduguri, Borno State”. February. Thematic series, UnSettlement: Urban Displacement in the 21st Century. Geneva: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.

IRC (2016). “Maiduguri urban context analysis brief”. International Rescue Committee. Available online (accessed 11 May 2021).

Jimme, M. A., Bashir, A. and Adebayo, A. A. (2016). “Spatial distribution pattern and terrain analysis of urban flash floods and inundated areas in Maiduguri Metropolis”. Journal of Geographic Information System 8(1):108-120.

Jimme, M. A., Musa, A. A. and Sambo, G. H. (2020). “Urbanization and its effects on the environment in Maiduguri Metropolis, Borno State, North East, Nigeria”. Jalingo Journal of Social and Management Sciences 1(3): 1-18, August. Available online.

Mandara, M. (2020). “Introduction of the Borno State 25 year development plan”. Presentation to the formal launching of the plan, Maiduguri, 14 November. Available online (accessed 11 May 2021).

Mayomi, I. and Mohammed, J. A. (2014). “A decade assessments of Maiduguri urban expansion (2002-2012) geospatial approach”. Global Journal of Geography, Geo-Sciences, Environmental Disaster Management, 14(2). Available online (accessed 11 May 2021).

Mercy Corps (2016). Motivations and Empty Promises: Voices of Former Boko Haram Combatants and Nigerian Youth. Portland, OR and Edinburgh, UK: Mercy Corps.

NSRP and V4C (2016). Masculinities, Conflict and Violence. Nigeria Country Report 2016. Nigeria Stability and Reconciliation Programme. Available online (accessed 11 May 2021).

Odihi, J. O. (1996). “Urban droughts and floods in Maiduguri: Twin hazards of a variable climate. Frankfurt: Berichte des Sonderforschungsbereichs 268, Volume 8: 303-319. Available online (accessed 11 May 2021).

PCNI (2016). Rebuilding the Northeast: The Buhari Plan, Volume 1: Emergency Humanitarian Assistance Social tabilization and Protection Early Recovery (Initiatives Strategies and Implementation Frameworks). Abuja: Presidential Committee on the Northeast Initiative.

Sebastine, A.I. & Obeta, A.D. (2015),The Amajiri Schools and National Security: A Critical Analysis and Social Development Implication. Global Journal of Management and Business Research: BEconomics and Commerce: Volume 15 Issue 5.

Stanford University (Last modified March 2018). Mapping Militant Organizations. “Boko Haram”.

UNEP (2004). Fortnam, M.P. and Oguntola, J.A. (eds), Lake Chad Basin, GIWA Regional assessment 43, University of Kalmar, Sweden.

Waziri, M. (2009). Spatial Pattern of Maiduguri City: Researchers’ Guide. Kano City: Adamu Joji Publishers.

[1] Waziri (2012).

[2] Bloch et al. (2015) categorised Nigeria’s settlements into five classes, based on their population size in 2010 – 5 million or more, 1 to 5 million, 500,000 to 1 million, 300,000 to 500,000, fewer than 300,000.

[3] Jimme, Bashir and Adebayo (2016).

[4] ICG (2014).

[5] DTM R12 Report on the 2 main urban areas in Jere LGA and Maiduguri Metropolitan Council (MMC).

[6] https://displacement.iom.int/nigeria

[7] Mayomi and Mohammed (2014).

[8] National Bureau of Statistics (2010).

[9] PCNI (2016).

[10] For example, the Borno Plastics Company and other smaller companies focusing on plastics production.

[11] IDMC (2018).

[12]PCNI (2016); IDMC (2018).

[13] IRC (2016).

[14] Rademaker et al. (2018).

[15] Fortnam and Oguntola (2004).

[16] ICRC (2018).

[17] Waziri (2009).

[18] The Borno State Urban Planning and Development Board was established in 2000 with responsibility for formulating and implementing planning schemes. Specifically, their mandate is for construction and maintenance of infrastructure, imposing fees, financing for projects, formulation of state policies for urban and regional planning (including initiation of urban master plans), and providing infrastructure such as roads, rain water and electricity in approved local plans. The Board reports to the Commissioner State Executive Council. The Board has a zonal officer or zonal manage in each LGA.

[19] https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2020/05/10/zulum-unveils-masterplan-to-expand-maiduguri-metropolis/

[20] Jimme, Musa and Sambo (2020).

[21] Mandara (2020).

[22] IRC (2016).

[23] Mercy Corps (2016).

[24] http://web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/553?highlight=boko+haram#note5

[25] https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/nigeria-s-super-camps-leave-civilians-exposed-terrorists

[26] Felbab-Brown (2020).

[27] Odihi (1996).

[28] Waziri (2009).

[29] Waziri (2009).

[30] NSRP (2016).

Hear Zara Ahmadu, a community engagement officer with the International Rescue Committee in Maiduguri, talk about the challenges facing the city and how ACRC can help address them through research into governance structures and supporting locally-driven solutions.

Header photo credit: International Rescue Committee

LATEST NEWS from ACRC

Streetlights in Lagos can boost safety and grow the economy – why not everyone benefits

Feb 24, 2026

Streetlighting plays a crucial role in public safety and security, and it promotes inclusive social and economic development by boosting local commerce, street businesses and community engagement.

In the shadow of Nairobi’s expansion: From peasants to paupers

Feb 4, 2026

In a new open access book, Peasants to Paupers: Land, Class and Kinship in Central Kenya, Peter Lockwood – former Hallsworth Fellow at The University of Manchester and now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Goettingen – tells the human stories behind Kenya’s rapid urban expansion and the families being left behind.

Crime-fighting in Lagos: Community watch groups are the preferred choice for residents, but they carry risks

Jan 30, 2026

Criminal activities have developed into a security crisis in Nigeria. Alongside the responses of security agencies such as the police and military, there has been a huge local response, with community groups mobilising in the face of criminal attacks.