Harare

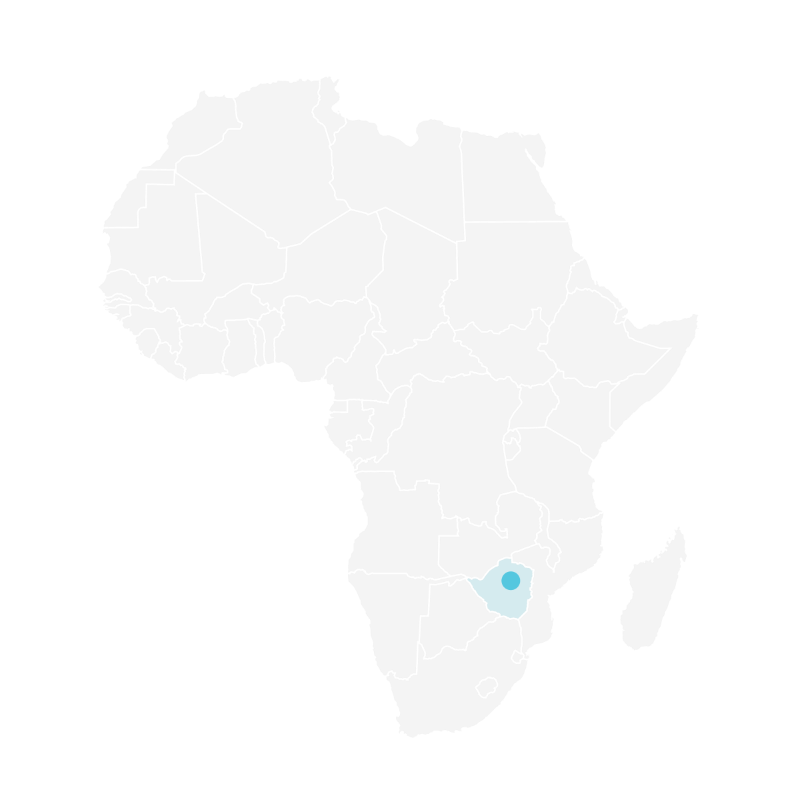

Harare is the capital city of Zimbabwe, positioned in the northeast of the country, and has an estimated population of 1.4 million.

Formerly known as Salisbury, Harare was officially declared a city in 1935 when its population had reached almost 20,000. At the time of Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, this had grown to 616,000. The lifting of institutional apartheid controls which restricted movement before independence was responsible for the population doubling between then and now.

Harare is undergoing rapid urbanisation, triggering manifold socio-economic and political challenges and putting strain on the built environment, with an estimated 33.5% of the urban population residing in informal areas.

Harare: City Scoping Study

Read the full study below, or download it as a PDF here.

Read now

African Cities Research Consortium

Harare: City Scoping Study

By George Masimba (Dialogue on Shelter Trust)

Urban Context

History of the city

Harare lies in the north-east of Zimbabwe tucked at the watershed plateau of two major rivers; Zambezi on the north and Limpopo on the south.[1] The area has prime agricultural soils offering Harare opportunities for agricultural activities in addition to the dominant manufacturing sector. It was previously known as Salisbury, and between 1953 and 1963 it was the capital of the Federation constituted by Nyasaland (Malawi), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). It was positioned at the core of the political and economic processes of the colonial establishment and witnessed an unprecedented growth in construction as a result.[2]

Harare’s demographic context

Harare was formerly known as Salisbury, which was declared a municipality in 1897. By 1935 its population had grown to nearly 20,000 and it was officially declared a city.[3] At the time of Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, Harare’s population was 616,000. Its current population is estimated to be 1.4 million while the entire metropolitan area raises this figure to 2.1 million.[4] The lifting of institutional apartheid controls that restricted movement prior to independence is responsible for the city’s population doubling in this time.[5]

Geography and physical expansion of the city

Harare Province is constituted by the City of Harare, Chitungwiza Municipality and Epworth Local Board. It has a sub-tropical climate and annually receives rains of between 470mm and 1350mm.[6] Due to its position on the highveld plateau, Harare’s average temperature hovers around 18oC, which is unusually low for the tropics. These climatic conditions support natural vegetation with musasa and jacaranda trees forming colourful canopies between October and November every year.[7] The city expanded after 1980 towards its peripheries in the south and south-west with the establishment of residential developments. Urban sprawl and informal land occupations can be explained by the unmet demand for affordable housing.

The city’s economy and its relation to other cities in the country

As the capital, Harare is where most of the country’s political and economic processes are concentrated. Estimates suggest that one in three Zimbabweans live in Harare, with the city’s economy contributing 40% of the national gross domestic product.[8] However Harare’s formal and informal economies have not been integrated and socio-spatial disparities remain deeply entrenched.[9]

The city acts as a major hub for the country’s road, rail and air transport networks, and is positioned strategically for trade and tourism. After independence in 1980, Harare inherited a robust manufacturing sector that was anchored by mining and agricultural activities.[10] However, starting in 1982, the country experienced recurrent episodes of disruptive weather patterns alongside ill-conceived macro-socio-economic policy decisions by the post-colonial government. In 1999, the entry of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) on the political scene presented complex political realities which further compounded the challenges in Harare and other urban centres.

Whilst Harare benefitted from significant infrastructure investments compared to other cities during the colonial and post-colonial periods, since 2000 there has been a decline in both physical and social amenities.[11] In addition to limited or absence of infrastructure and services in some areas, authorities have also failed to maintain existing infrastructure.

Political context

National political context

Since gaining independence in 1980, Zimbabwe has been under the political leadership of the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), led for most of these years by Robert Mugabe until he was deposed in November 2017.[12] Currently, the party and the country is led by Emmerson Munangagwa. ZANU-PF’s political foundation is rooted in Marxist thinking although many have questioned the extent to which its rule has consistently reflected Marxist ideology .[13] Elections have been held as per constitutional provisions but they have unfailingly been contested with opposition alleging massive rigging and systematic use of violence as a political weapon. These accusations have led some to conclude that ZANU-PF’s bigger plan has always been inclined towards instituting a one-party state.[14]

History of relations between city and national government

Harare’s politics has remained hotly contested for nearly three decades, since the formation of the country’s biggest opposition party.[15] Land and tribal issues have generally been at the heart of the country’s populist politics and have dictated the redistribution agenda .[16] Urban councils are largely dominated by the opposition while the ruling party’s power is rooted in the countryside. Land allocations across both the rural-urban divide have thus been politicised with the opposition accused of favouring its urban constituency.[17] To counter this, the ruling party has established its own loyalists within the city, allowing them to illegally occupy council or state land without the requisite town planning approvals and basic services. The net effect of this political configuration has been that the national and local governments perpetually function at cross-purposes.[18] Nowhere have these contestations been more evident than in cities, hence Harare has become an inconvenient symbol of the threat to ZANU-PF’s hegemony.

Current significance of the city to the country

Zimbabwe is currently governed under a 2013 National Constitution, whose promulgation was a compromise produced through fierce bargaining between the two major political parties, ZANU-PF and MDC.[19] Zimbabwe embarked on a programme of decentralisation after independence, and the 2013 constitution provided a legal framework and hence the impetus for realising this objective. For instance, a devolution agenda has found a new resurgence within Mnangagwa’s administration although some have questioned the capacity, motivation and intent for this political trajectory.[20] The Commonwealth Local Government Forum observes that in addition to the lack of political will, there is restricted fiscal space for local government structures to deliver on the national aspirations of the devolution agenda.[21]

Urban challenges

The city and the spatial challenges

Consistent with trends in cities in the global South, Harare is witnessing rapid urbanisation triggering manifold socio-economic and political challenges, straining the built environment. The built-up areas in Harare increased from 279.5km2 in 1984 to 445km2 in 2018, with most of these land-use and land cover changes towards the south-west where vast areas of high-density and often informal residential developments have emerged.[22] Yet, weakened and corrupt land administration systems have undermined the municipal government’s ability to fully derive value from the city’s growth. There has been a rapid increase in informal settlements in Zimbabwe’s urban settings and in 2018 the World Bank estimated that 33.5% of the urban population reside in informal areas. Meanwhile, citywide slum settlement profiles conducted under the Harare ‘slum upgrading project’ have also classified 63 neighbourhoods as ‘slums’.[23]

Shack densities in Harare’s informal settlements are lower than other cities in the region, highlighting the potential for in-situ upgrading. Predictably, the growth in informal housing has prompted other forms of informalities downstream, highlighting strong interdependencies between different urban systems in the city. For example, informal areas are typically excluded from the formal services grid due to exclusionary planning frameworks that are grounded in the country’s colonial history, and hence residents resort to informal practices to access amenities such as water, sanitation, education and even health services. Shallow wells and pit latrines substitute for water and sanitation services. Meanwhile, existing planned suburbs have not escaped infrastructure challenges, and old water and sanitation systems in places such as Mbare (the central market area) have collapsed due to over-crowding.[24] The city’s waste-water treatment plants have a design capacity of 208,000 m3/d compared to inflows of 300,000 m3/d, in turn, illustrating potential water quality issues.[25]

Redevelopment challenges: Contested visions, displacement and evictions

Harare’s response to the levels of growing urban informality has relied on evictions and demolitions as the default solution as demonstrated by the government-led campaign Operation Murambatsvina (“Drive-Out-Filth”) in 2005 and more recently Covid-19 lockdown-induced displacements.[26] The same exclusionary practices have also befallen the informal economy in the capital of Harare. A study commissioned by the World Bank confirmed that vending activities are viewed as a nuisance and criminalised, rather than seen as productive processes contributing to the urban economy.[27] While the country’s pre-colonial urban history accounts for segregationist planning responses, there has also been ill-informed political imperative within post-independence city authorities making them gravitate towards modernist planning ideals that are often not aligned with the prevailing socio-economic circumstances.[28] Idealistic city visioning processes that set impractical minimum housing and infrastructure standards are classic examples.

Socio-economic challenges: Poverty, informal economy and lack of access to basic services

Urban poverty has become entrenched and an urban livelihoods assessment established that out of ten provinces, Harare had the highest proportion of households that consumed poor diets.[29] The Covid-19 pandemic has further compounded the urban socio-economic challenges.[30] Harare health facilities were over-stretched by the pandemic, and physical distancing also proved to be impractical in Harare with residents queuing for water at boreholes, especially in low-income neighbourhoods.[31] Despite these deteriorating conditions, Harare continues with visioning processes that imagine ‘a world class city by 2025’.[32] Harare’s urban challenges have also sparked attendant environmental problems, further plunging the city into wide-ranging crises. The ecological footprint of urban growth has been very evident in the city.[33]

Environmental challenges in Harare

In 1984 vegetation covered approximately half of the Harare total province’s area, but by 2018 this had been reduced by almost 50%.[34] Persistent power cuts have also contributed to the changes in vegetation cover due to excessive felling of trees for wood fuel. As most of the land use activities are being taken up by residential developments, Harare has also failed to cope with managing increased waste generation, resulting in land, air and water pollution. The city has been accused by the Environmental Management Agency of discharging raw effluent into Lake Chivero – the capital’s main water supply reservoir, with disastrous downstream implications on the water body’s flora and fauna.[35]

Climate change has also had serious consequences on Harare with recurrent droughts adversely affecting both water supply and urban agriculture activities. The Urban Livelihoods Assessment revealed that households practising urban agriculture in Harare accounted for 31.8% of the total urban households in 2016 but in 2019 this figure had declined to 17.1% and this was largely attributable to poor rainy seasons.[36] In 2020 a similar assessment revealed that Harare accounted for 50% of the national population that was food insecure, further reinforcing the urban dimensions of climate change-induced adverse rainfall pattern variations in the country.[37] Poor drainage in the capital of Harare has also failed to contain heavy downpours with the 2021 season’s rains, destroying housing and displacing affected residents in one of the high-density (low-income) suburbs in the city.[38] These interconnected challenges underscore the centrality of multiple nexuses and actors within the city’s sub-systems which the African Cities Research Consorrtium is focused on with its political settlement and city of systems analysis approaches.

Political challenges

National-local political contestations in Harare

Zimbabwe’s political landscape remains predominantly dualised with ZANU-PF controlling rural areas while the MDC enjoys comfortable support in cities and the attendant struggles manifest in urban governance processes.[39] Central-local contestations have significantly altered administration of urban centres in Zimbabwe.[40] The ruling party, ZANU-PF has been accused of using national level institutions, especially the Ministry of Local Government to influence local authorities and in some cases even invoking questionable ministerial powers to arbitrarily depose elected urban councils.4[41]

Whimsical debt cancellations by the Ministry of Local Government which cost Harare two years’ revenue is an example of centre-led interventionist politics that plunged service delivery into chaos in 2013.[42] A poor institutional framework has contributed to poor service delivery.[43] The intended political objective of these manoeuvres has been to win back the urban vote, but the status of the electoral space has not fundamentally changed since the entry of MDC in 1999 on the political scene. The net effect of these centre-local tensions has been the continued deterioration of urban services which has resulted in frequent water cuts, sewage blockages and dilapidated road infrastructure. The 2008 cholera outbreak in Harare, which resulted in nearly 5000 deaths nationwide, can be attributed to the city’s urban crises and issues within the social services function managed by urban councils.

Political contestations and the implications on exclusion

Elections in urban centres have also been rendered inconsequential as elected officials are frequently frustrated, suspended or in some instances expelled for political reasons.[44] This intentional disruption of urban governance processes has, in turn, generated multiple informalities. Informal power structures that are either officially or unofficially controlled by ZANU-PF have emerged, setting the scene for parallel arrangements for urban services provision. In addition, self-provisioning of urban services by residents frustrated by the incapacitated urban councils has also led to the emergence of informal settlements. Old housing facilities built during pre-colonial times in suburbs like Mbare have, for instance, seen the collapse of aging water and sanitation systems.[45] At the end of July 2008, the country’s inflation rate hit a record high of 231 million percent.[46] In 2016 a citywide slum profiling and participatory mapping exercise had produced an updated list of 63 informal settlements within the capital.[47] Yet, this was ten years after the 2005 nationwide Operation Murambatsvina (“Drive-Out-Filth”) which evicted and displaced 700,000 people in informal housing in urban centres.[48] More recently, in 2019 Harare was ranked amongst the three provinces with the lowest average household income out of the country’s ten provinces, with an average of US$55.31/month against an average total consumption poverty line of US$101.06.[49] These trends are expected to continue and worsen as a result of Covid-19.[50]

African Cities Research Consortium: Potential added value in Harare

The contested nature of Zimbabwean politics has contributed to intractable service delivery challenges in cities, including Harare. While social and physical infrastructure have been adversely affected in Harare, land access has been the most politicised. These challenges necessitate serious policy and practice-related shifts that are buttressed by tested research. The African Cities Research Consortium’s action research initiative anchored on the two theoretical frameworks – city of systems and political settlement analysis – has been crafted to respond to these complex urban challenges. Political settlement analysis, for instance, and its key notions of coalitions, capacity and context has potential to help extend understandings of Harare’s challenges beyond the immediacy of particular political contestations.[51]

Similarly, the city of systems approach which views the city as a series of inter-related systems, (for example water, transportation, education) draws attention to the interconnected nature of the complex problems bedeviling cities. In Harare, this can include how informalised and politicised land access practices are crucially influencing the city’s materiality. The introduction of the concept of domains representing arenas of power, policy, practice and knowledge production will illuminate the contested framings and strategic alliances animating urbanisation in Harare. These domains are occupied by different actors with varied interests and ideas, and will include land-use, housing and informal settlements.

References

ACC and UK Aid. (2015). Urban infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa – harnessing land values, housing and transport.

Awumbila, M. (2017). “Drivers of migration and urbanization in Africa: Key trends and issues”. Paper presented at United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Sustainable Cities, Human Mobility and International Migration, New York, 7-8 September. Available online (accessed 1 June 2021).

Brown, C. and Chasokela, E. (2019). “EMA blames Chivero pollution on council”. The Herald, 9 May. Available online (accessed 10 February 2021).

Chakunda, S., 2015. Central-local government relations: implications on the autonomy and discretion of Zimbabwe’s local government. Political Sci Public Aff, 3(1), pp.1-4.

Cheetham, R. J. (2011). Infrastructure and Growth in Zimbabwe: An Action Plan for Sustained Strong Economic Growth (Vol. 1). Tunis: African Development Bank Group.

Chigudu, S., 2020. The political life of an epidemic: cholera, crisis and citizenship in Zimbabwe. Cambridge University Press.

Chigwata, T. C. (2019). “Decentralisation and constitutionalism in Zimbabwe”. In C. M. Fombad and N. Steytler (eds.), Decentralisation and Constitutionalism in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.302.

Chikowore, E. (1993). “Harare: Past, present and future”. Harare: The Growth and Problems of the City. Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publications.

Chikwawawa, C. (2019). “Constitutionalisation and implementation of devolution in Zimbabwe”. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 9(3): 1-7.

Chirisa, I. and Dumba, S. (2012). “Spatial planning, legislation and the historical and contemporary challenges in Zimbabwe: A conjectural approach”. Journal of African Studies and Development 4(1): 1-13.

Chirisa, I., Bandauko, E. and Mutsindikwa, N. T. (2015). “Distributive politics at play in Harare, Zimbabwe: Case for housing cooperatives”. Bandung, 2(1): 1-13.

Chirisa, I., Mutambisi, T., Chivenge, M., Mabaso, E., Matamanda, A. R. and Ncube, R. (2020). “The urban penalty of COVID-19 lockdowns across the globe: Manifestations and lessons for Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa”. GeoJournal, 1-14.

City of Harare (2016). “State of the City Address – 1st March 2016 by his Worship Mayor Benard Manyenyeni”.

City of Harare (2017). City of Harare Results Based Strategic Plan (2017 – 2020).

Commonwealth Local Government Forum (2016). The Constitution of Zimbabwe 2013 as a Basis for Local Government Transformation: A Reflective Analysis. Strengthening Capacity for Local Governance and Service Delivery in Zimbabwe. CLGF Southern Africa Regional Programme.

Dialogue on Shelter (2020). Policy advice to respond to Covid-19 in urban informal settlements in Zimbabwe.

Dialogue on Shelter Trust, Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation and City of Harare (2014). Harare Slum Profile Report. London: IIED.

Dialogue on Shelter Trust, Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation and City of Harare (2016). End Evaluation of the Harare Slum Upgrading Programme (HSUP).

DFID (2017). DFID Zimbabwe Country Engagement Final Scoping Report. A.ZIM.PRE.01. Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development.

Government of Zimbabwe (2011). Harare Provincial Profile. Parliament Research Department.

Government of Zimbabwe (2012). Zimbabwe Census 2012 National Report. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency.

Government of Zimbabwe (2019). Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) 2019 Urban Livelihoods Assessment. Harare.

Government of Zimbabwe (2020). Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) 2020 Urban Livelihoods Assessment.

Gwaze, V. (2021). “The curse of city flood”. The Sunday Mail, 23 May. Available online (accessed 10 February 2021).

Hunter, J., Chitsiku, S., Shand, W. and Van Blerk, L. (2020). “Learning on Harare’s streets under COVID-19 lockdown: Making a story map with street youth”. Environment and Urbanization, 33(1): 31-42.

IBRD (1958). Economic position and prospects of the Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Department of Operations – Europe, Africa and Australasia.

IBRD. (1964). The economy of southern Rhodesia. Department of Operations – Africa

Kamete, A. Y. (2013). “On handling urban informality in southern Africa”. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 95(1): 17-31.

Manase, G., Mulenga, M. and Fawcett, B. (2001). “Linking urban sanitation agencies with poor community needs: A study of Zambia, Zimbabwe and south Africa”. London: DFID Knowledge and Research Project.

Marondedze, A. K. and Schütt, B. (2019). “Dynamics of land use and land cover changes in Harare, Zimbabwe: A case study on the linkage between drivers and the axis of urban expansion”. Land, 8(10):155.

Marumahoko, S., Afolabi, O. S., Sadie, Y. and Nhede, N. T. (2020). “Governance and urban service delivery in Zimbabwe”. Strategic Review for Southern Africa 42(1): 41-68.

Matamanda, A. and Chirisa, I. (2014). “Ecological planning as an inner-city revitalisation agenda for Harare, Zimbabwe”. City, Territory and Architecture, 1(1): 1-13.

Mbiba, B. On the periphery: missing urbanisation in Zimbabwe. www.africaresearchinstitute.org Accessed 12 February 2021.

McGregor, J. (2013). “Surveillance and the city: Patronage, power-sharing and the politics of urban control in Zimbabwe”. Journal of Southern African Studies, 39(4): 783-805.

McGregor, J. and Chatiza, K.(2020). “Partisan citizenship and its discontents: Precarious possession and political agency on Harare City’s expanding margins”. Citizenship Studies, 24(1): 17-39.

McGregor, J. and Chatiza, K. (2020). Geographies of urban dominance: The politics of Harare’s periphery.

Mhlanga, B. (2021). “Floods displace 30 families in Budirio”. NewsDay 16 January. Available online (accessed 10 February 2021).

Mitullah, W. V. (2003). “Street vending in African cities: A synthesis of empirical finding from Kenya, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Uganda and South Africa”. Background paper for the 2005 World Development Report. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Moore, D. (2018). “A very Zimbabwean coup: November 13-24, 2017”. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 97(1): 1-29.

Muchadenyika D. (2015). Slum upgrading and inclusive municipal governance in Harare: New perspectives for the urban poor.

Muchadenyika, D. (2015). “Land for housing: a political resource – reflections from Zimbabwe’s urban areas”. Journal of Southern African Studies, 41(6): 1219-1238.

Muchadenyika, D. and Williams, J .J. (2020). “Central–local state contestations and urban management in Zimbabwe”. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 38(1): 89-102.

Muchadenyika, D. (2020). Seeking urban transformation: Alternative urban futures in Zimbabwe. Weaver Press.

Multi Donor Trust Fund – MDTF (2008). Zimbabwe Emergency Recovery Program, Draft 2, September, Harare.

Munzwa, K. and Wellington, J. (2010). “Urban development in Zimbabwe: A human settlement perspective”. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 5(14): 120-146.

Muronda, T. (2008). “Evolution of Harare as Zimbabwe’s Capital City and a major Central Place in Southern Africa in the context of by Bylands model of settlement evolution”. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning 1(2): 034-040.

Mushamba, S., (2010). “The powers and functions of local government authorities”. In J. de Visser, N. Steytler and N, Machingauta (eds.), Local Government Reform in Zimbabwe: A Policy Dialogue, Bellville: Community Law Centre, University of the Western Cape, pp. 101-120.

Mushamba, S., Bhoroma, L., Chirisa, I. and Chaumba, A. (2014). “The dynamics of devolution in Zimbabwe: Abriefing paper on local democracy”. Harare: ActionAid Denmark

Nhapi, I. (2009). “The water situation in Harare, Zimbabwe: A policy and management problem”. Water Policy 11: 221-235.

Pahwaringira, L., Chaminuka, L. and Muranda-Kaseke, K. (2015). The Impacts of Water Shortages on Women’s Time-Space Activities in the High-Density Suburb of Mabvuku in Harare. wH2O: The Journal of Gender and Water, 4(1), p.8.

Potts, D. (2011). “’We have a tiger by the tail’: Continuities and discontinuities in Zimbabwean city planning and politics”. Critical African Studies, 4(6): 15-46.

Satterthwaite, D. (2007). The transition to a predominantly urban world and its underpinnings (No. 4). IIED.

Shaw, W. H. (1986). “Towards the one-party state in Zimbabwe: A study in African political thought”. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 24(3): 373-394.

Siavhundu, T. (2019). New Zimbabwe Parliament Project Progresses. www.pmworldlibrary.com Accessed 10 February 2021.

Stoneman, C. (1990). “The industrialisation of Zimbabwe – past, present and future”. Afrika Focus 6(3-4).

Tibaijuka, A. K. (2005). Report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina by the UN Special Envoy on Human Settlements Issues in Zimbabwe New York: United Nations

UN-Habitat. (2020). World Cities Report – The Value of Sustainable Urbanisation. Nairobi.

Watson, V. (2009). “‘The planned city sweeps the poor away…’: Urban planning and 21st century urbanisation”. Progress in Planning 72(3):151-193.

We Pay You Deliver Consortium. (2017). State of service delivery report (Zimbabwe): Cities at the crossroads. Technical Report.

World Bank (2020). Covid-19 to add as many as 150 million extreme poor by 2021. www.worldbank.org Accessed 10 February 2021.

World Bank (2021). “Population living in slums (percentage of urban population) – Zimbabwe”. Available online (accessed 1 June 2021).

Zeiderman, A., Kaker, S., Silver, J., Wood, A. and Ramakrishnan, K. (2017). Urban Uncertainty: Governing Cities in Turbulent Times. London: LSE Cities.

Zinyama, T. and Chimanikire, D. P. (2019). “The nuts and bolts of devolution in Zimbabwe – designing the provincial and metropolitan councils”. African Journal of Public Affairs, 11(2): 148-176.

[1] Government of Zimbabwe (2011).

[2] International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) (1958).

[3] Muronda (2008).

[4] Government of Zimbabwe (2012).

[5] Munzwa and Wellington (2010); and Potts (2011).

[6] Marondedze and Schütt (2019).

[7] Government of Zimbabwe (2011).

[8] Government of Zimbabwe (2012).

[9] Chikowore (1993).

[10] Cheetham. (2011); and Stoneman (1990).

[11] DFID (2017).

[12] Moore (2018).

[13] Shaw (1986); and Stoneman (1990).

[14] Shaw (1986).

[15] McGregorand Chatiza (2020).

[16] Chirisa, Bandauko, and Mutsindikwa (2015; and Muchadenyika (2015).

[17] Muchadenyika (2015).

[18] Muchadenyikaand Williams (2020).

[19] Mushamba et al. (2014).

[20] Chikwawawa (2019); Chigwata (2019); and Zinyama and Chimanikire (2019).

[21] Commonwealth Local Government Forum (2016).

[22] Marondedze and Schütt (2019).

[23] City of Harare (2016); and Dialogue on Shelter (2020).

[24] Manase, Mulenga, and Fawcett (2001).

[25] Nhapi (2009).

[26] Dialogue on Shelter (2020); and Tibaijuka (2005).

[27] Mitullah (2003).

[28] Chiris and Dumba (2012); Kamete (2013); Watson (2009); and Zeiderman et al. (2017).

[29] Government of Zimbabwe (2019).

[30] Chirisa et al. (2020); and Hunter et al. (2020).

[31] Chirisa et al. (2020).

[32] City of Harare (2016); and City of Harare (2017).

[33] Matamanda and Chirisa (2014).

[34] Marondedze. and Schütt (2019).

[35] Brown and Chasokela. (2019).

[36] Government of Zimbabwe (2019).

[37] Government of Zimbabwe (2020).

[38] Gwaze (2021); and Mhlanga (2021).

[39] Marumahoko et al. (2020); and Mushamba (2010).

[40] Muchadenyika and Williams (2020)

[41] McGregor (2013).

[42] Marumahoko et L. (2020).

[43] Nhapi. (2009).

[44] McGregor (2013).

[45] Dialogue on Shelter Trust, Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation and City of Harare (2014). Harare Slum Profile Report, Harare Slum Upgrading Project.

[46] Multi Donor Trust Fund – MDTF (2008). Zimbabwe Emergency Recovery Program, Draft 2, September, Harare.

[47] Dialogue on Shelter Trust, Zimbabwe Homeless People’s Federation and City of Harare (2014). Harare Slum Profile Report, Harare Slum Upgrading Project

[48] Tibaijuka, A. K. (2005). Report of the Fact-Finding Mission to Zimbabwe to assess the Scope and Impact of Operation Murambatsvina by the UN Special Envoy on Human Settlements Issues in Zimbabwe. New York: United Nations.

[49] Government of Zimbabwe (2019). Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) 2019 Urban Livelihoods Assessment.

[50] World Bank (2020).

[51] Chigwata (2019); Muchadenyika, and Williams (2020).

Hear from our Harare scoping study author, George Masimba, and ACRC’s action research director, Beth Chitekwe-Biti, as they discuss the key takeaways from the study and how the consortium can support crucial policy change in the city.

LATEST NEWS from ACRC

Streetlights in Lagos can boost safety and grow the economy – why not everyone benefits

Feb 24, 2026

Streetlighting plays a crucial role in public safety and security, and it promotes inclusive social and economic development by boosting local commerce, street businesses and community engagement.

In the shadow of Nairobi’s expansion: From peasants to paupers

Feb 4, 2026

In a new open access book, Peasants to Paupers: Land, Class and Kinship in Central Kenya, Peter Lockwood – former Hallsworth Fellow at The University of Manchester and now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Goettingen – tells the human stories behind Kenya’s rapid urban expansion and the families being left behind.

Crime-fighting in Lagos: Community watch groups are the preferred choice for residents, but they carry risks

Jan 30, 2026

Criminal activities have developed into a security crisis in Nigeria. Alongside the responses of security agencies such as the police and military, there has been a huge local response, with community groups mobilising in the face of criminal attacks.