By Rosebella Apollo, ACRC research uptake officer

With ACRC’s aims to contribute towards and drive evidence-informed decisionmaking (EIDM) in the African continent, I was delighted to represent the consortium during the Evidence 2023 conference, held from 13 to 15 September 2023 in Entebbe, Uganda.

The Evidence conference is a biannual summit, organised by the Africa Evidence Network (AEN) – a pan-African network that seeks to entrench a culture of evidence uptake, in a bid to address poverty and inequality in Africa. AEN links potential users with timely and relevant evidence to inform decisionmaking, policymaking, practices and programmes. This year’s event marked over ten years of the network’s existence, with a membership of 5,563 across the globe.

Convening a total of 713 delegates from 63 countries, the summit unpacked topics including the decolonisation of evidence, and dominating discussions was the key issue of the relevance of indigenous knowledge in the evidence. Here I highlight some of my main takeaways from deliberations on indigenous knowledge production during the conference.

Rejigging evidence production

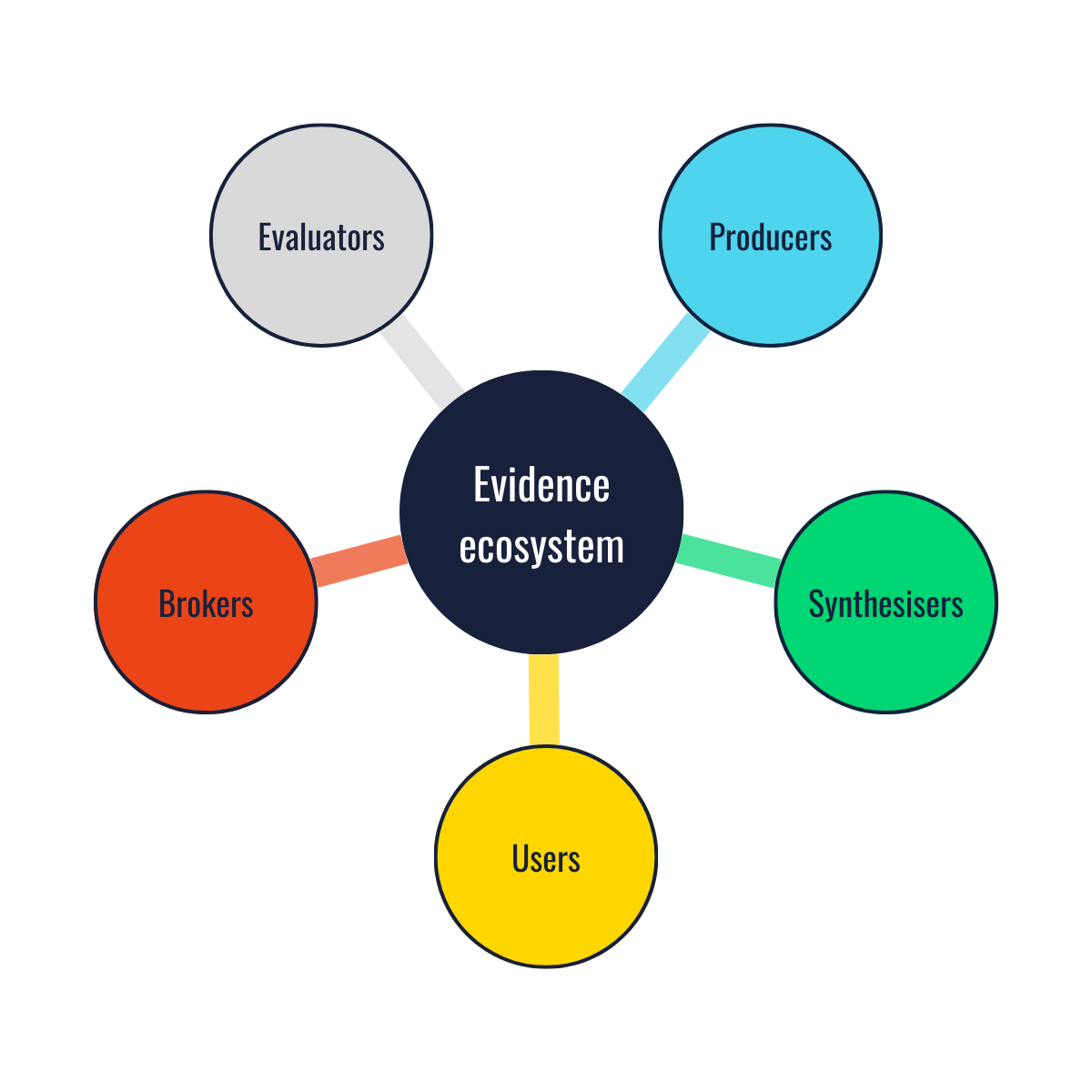

The evidence ecosystem in Africa is made up of evidence producers, synthesisers, users, brokers and evaluators. For meaningful evidence-informed decision and policymaking, it is critical that relevant, appropriate and applicable knowledge is generated in a transparent manner.

The evidence ecosystem in Africa

With evidence users calling for a paradigm shift – to more closely evaluate the credibility of evidence sources, evidence production strategies and nature of evidence generated – transparency is key to meeting their demands. In this context, the value and relevance of indigenous knowledge in stimulating evidence production cannot be overemphasised. It is therefore important to embed strategies that prioritise indigenous knowledge and amplify African culture, values and beliefs.

Power and agency in evidence generation

Current power structures in the evidence landscape propagate Western ideologies and institutions and subjugate African culture, ostensibly exacerbating power imbalances between the global North and South. While these power dynamics have been upheld as “gold standards” of evidence generation, they do not necessarily translate into valid and credible evidence. Dominance of Western approaches in research often compromises evidence outcomes, translating into wrong conclusions and defunct developmental results. Therefore, adopting African ways of generating knowledge must be at the centre of EIDM practices in the continent.

To generate credible and relevant evidence, local communities’ agency and voice must drive the processes. Using practical evidence generation solutions – that complement prevailing cultural practices and empower indigenous people to retain their agency and remain dignified during research – will ensure that indigenous knowledge reflects realities on the ground.

However, researchers often wield more power than their subjects, which compromises the generation of indigenous knowledge. Reconstructing and restructuring power relations could help overcome this imbalance and its associated challenges. This could be achieved through building relationships with respondents, enhancing feedback mechanisms for taking evidence to the community, and prioritising community aspirations in accessing, owning and using data.

Rosebella Apollo speaking at the Evidence 2023 conference in Entebbe, Uganda

The African relational paradigm in particular has been pivotal in interrogating the knowledge and perceptions of realities in the African continent. The post-colonial paradigm advances a consideration of multiple epistemologies in research, particularly taking into account historical and cultural perspectives. The relational epistemology articulates African (indigenous) ways of knowing, such as ingrained practices, relationships, ways of doing things, systems and networks that shape reality in African contexts.

Examining overreliance on specific research methodologies and processes of knowledge production could give an opportunity to better integrate lessons from indigenous systems of knowledge production, incorporating the pervasive African cultures, languages, values and traditions.

Equity and inclusion for indigenous knowledge

Undervaluing African cultures, traditions and ways of knowledge production has detrimental effects, both on communicating African problems and on identifying lasting solutions to challenges in the African continent. Reflexivity in unpacking knowledge is key to identifying biases and addressing systemic barriers, such as attitudes, language, traditions, policies and practices that could challenge the validity and reliability of indigenous knowledge.

To safeguard integrity and mitigate against biases associated with indigenous knowledge, participation that values contribution from local contexts is necessary. Inclusive approaches during research will ensure that no one is left behind. Through such inclusivity, voices of communities and marginalised groups will be amplified.

To strengthen the generation of indigenous knowledge, development agencies should shift power and resources, and allow ownership from local institutions and people to lead evidence generation. Shifting mindsets towards appreciating knowledge that is “Made in Africa” and valuing local evidence differently will build demand for indigenous evidence.

Packaging indigenous knowledge for underserved communities

Best practices in EIDM recommend a reporting back-loop that disseminates evidence in communities where it was gathered. Traditionally, packaging of evidence for users includes formats such as policy briefs, scientific publications, short videos and presentations. Despite associated risks, such as safety and security concerns, invasion of privacy and a digital divide, advancements in technology have catalysed evidence packaging and dissemination.

However, some of these widely used formats may exclude communities from accessing and using evidence. This highlights the need to think about alternative approaches to packaging and disseminating evidence, in order to expand reach. Storytelling, folklore and performances are some of the strategies proposed for expanding reach of evidence within indigenous communities.

Storytelling as communication tool translates research evidence into songs, poems and dance, providing an alternative pathway for packaging and transferring knowledge into action amongst indigenous and underserved groups.

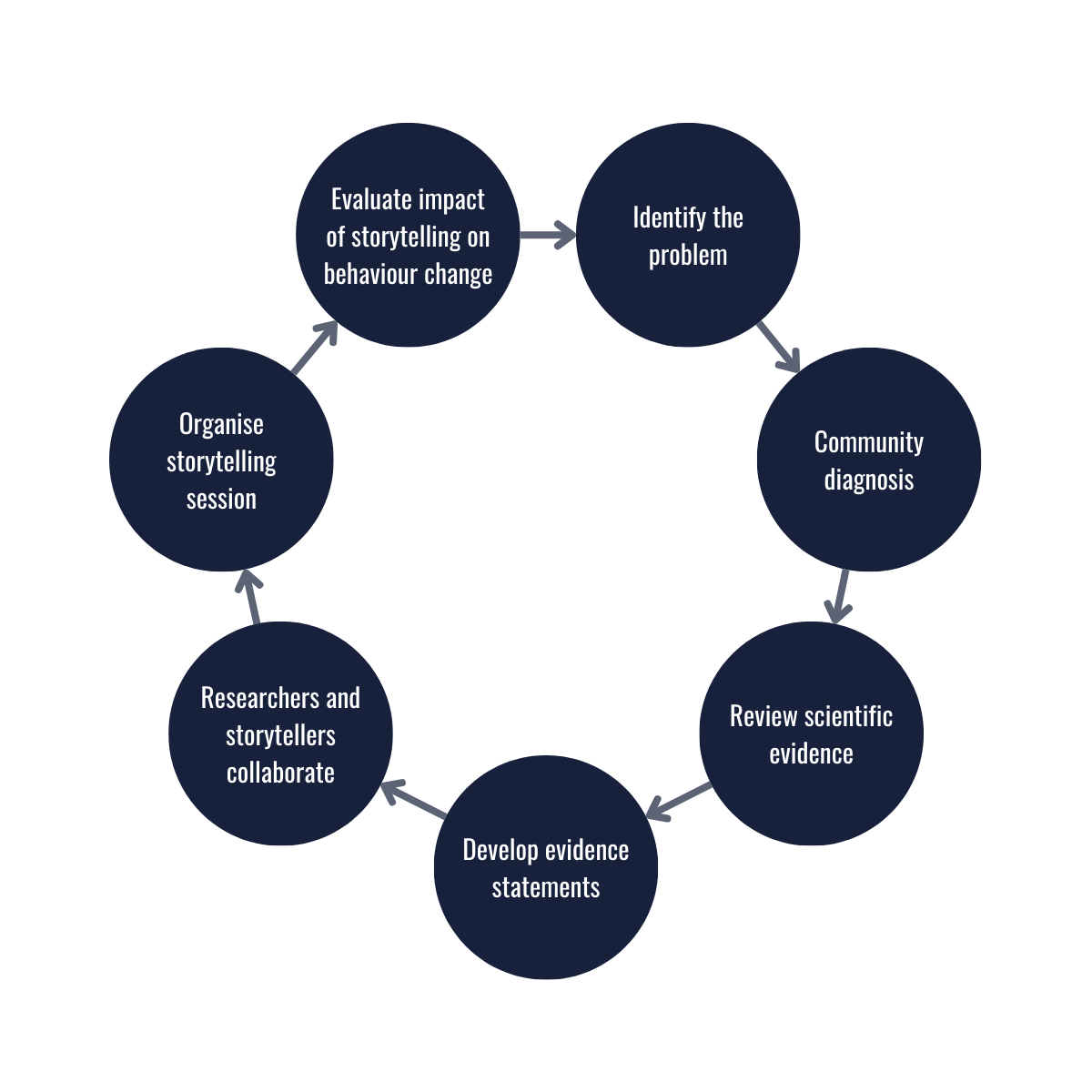

Evidence Tori Dey: Seven-step evidence-based storytelling framework (eBASE Africa 2023)

For example, using “Evidence Tori Dey” – a seven-step evidence-based storytelling framework – the charity eBASE Africa has disseminated evidence on sexual and gender-based violence, Covid-19, menstrual hygiene, and education to communities in Cameroon. Storytelling replaces complex research evidence terminologies with simple and emotionally appealing use of poems, songs and drama, in languages that can be understood by communities.

In collaboration with key stakeholders, local and culturally appropriate traditional methods should be used to communicate evidence and effective interventions. The storytelling methodology in particular could be adapted for taking evidence from ACRC research back to local communities, which is an integral part of building capacity for local communities to champion for urban reforms.

Read Rosebella’s article on politically informed decision and policymaking for resilient African cities via the Africa Evidence Network website.

Header photo credit: Rosebella Apollo

Note: This article presents the views of the author featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.