Since 2009, communities in Borno State, Nigeria, including Maiduguri, have been experiencing violent attacks perpetrated by the Boko Haram insurgent group. In response to the threats of insurgency, the government deployed its security apparatus to secure the state. Over time, it became evident that the military and police could not effectively deal with the insurgency. Thus, in 2013, residents of Maiduguri formed the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) to complement the counterinsurgency efforts of the state security forces.

Though other informal security providers (ISPs) existed in Maiduguri prior to the onset of the insurgency, the work of the CJTF consolidated and reaffirmed the relevance of community policing. So, a hybrid form of “security architecture” emerged – with the formal security forces depending on the informal security providers’ local knowledge of the environment and intelligence-gathering capabilities.

The synergy between the state and non-state security providers appears to have brought relative calm to Maiduguri. However, the long years of insurgency created favourable conditions for crime to thrive. Thus, as the insurgent threats receded, there was an evident surge in other forms of criminality in the city, necessitating the intensification of community policing efforts.

How have the (in)formal security providers contributed to addressing the worsening criminal activities in the city? Fieldwork in Maiduguri revealed the types of (in)formal security providers that exist in the city and their roles in urban safety and security. This has implications for urban security reforms in Nigeria.

Figure 1: Location of Maiduguri

Mapping the complex landscape of (in)formal security provision in Maiduguri

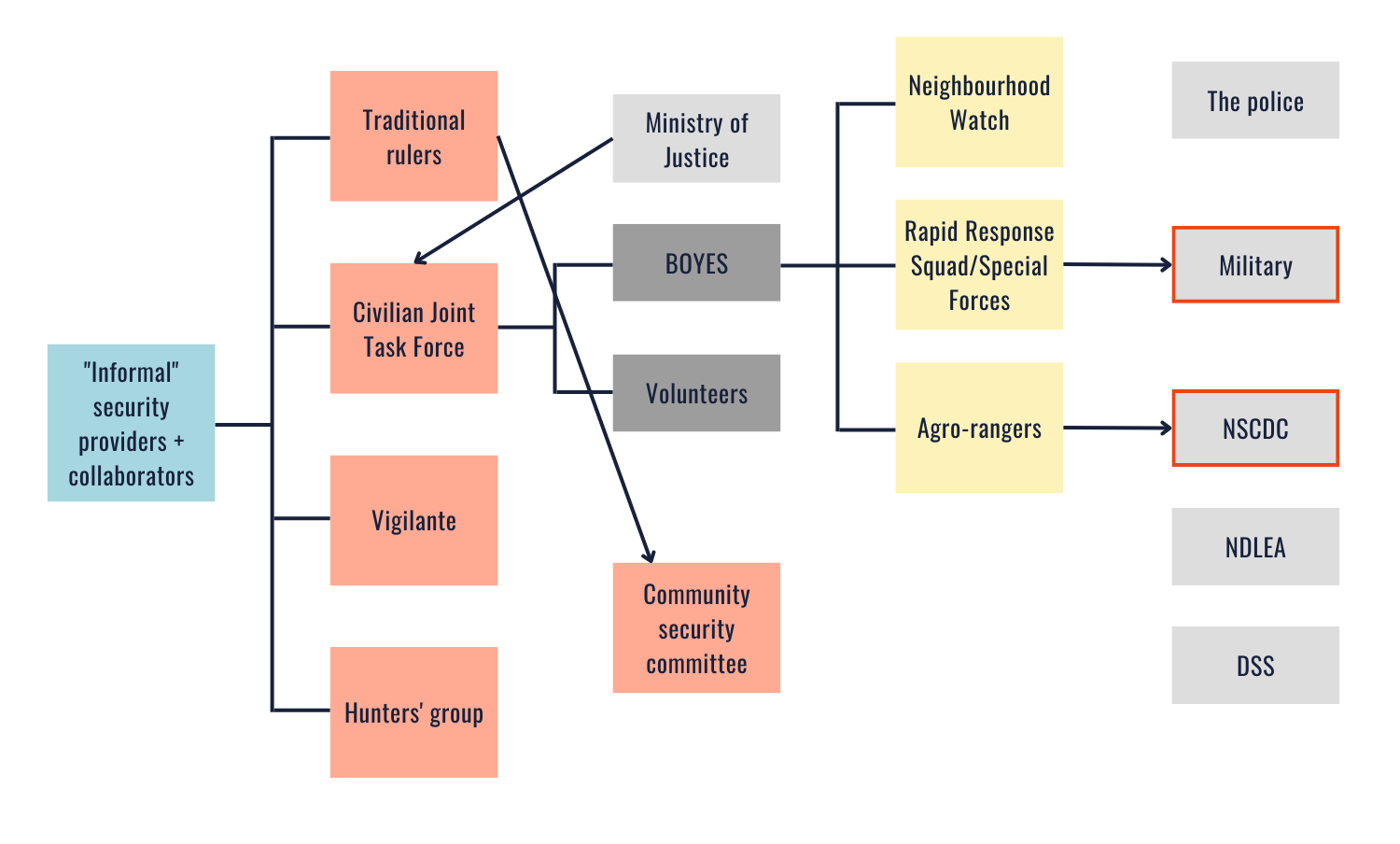

The configuration of community policing in Maiduguri presents a complicated network of actors, roles, levels of interactions, engagement and patronage (see Figure 2). On the one hand, there are the informal security providers, like the urban traditional rulers (Bulama, Lawan), community security committees, vigilante groups, hunters’ groups and the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF). On the other hand, there are formal security providers, like the military, police, the Department of State Services (DSS), the Nigerian Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC) and the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA).

Collectively, the security providers often converge on broader platforms, such as the Police Community Relations Committee (PCRC) and state security council, to forge partnerships for urban safety. More specifically, the traditional rulers act informally as “chief security officers” of their communities. They are responsible for constituting the community security committees, in order to partner with them in ensuring residents’ safety.

The vigilante and hunters’ groups have a long and varied history in Nigeria. Vigilantes engage in crime prevention and control at the neighbourhood level, while hunters’ groups deploy their game hunting expertise to curb criminal activities in the forests and fringes of the city. In Maiduguri, however, the hunters’ groups are also involved in urban security.

Conversely, the Civilian Joint Task Force is a name coined to portray the collaborative efforts of ordinary community members (civilians) and the military in combating violence. The CJTF also exists in other parts of Nigeria, where it is mainly engaged in preventing and managing rural conflicts. In Maiduguri, the CJTF is currently made up of two groups – the volunteers and those absorbed into the newly created Borno Youth Empowerment Scheme (BOYES). The Department of State Services vets and profiles the volunteers recruited into BOYES, while the Ministry of Justice regulates the activities of the CJTF.

Figure 2: The complex landscape of (in)formal security provision in Maiduguri

The creation of BOYES is an attempt by the state government to “formalise”, restructure and legitimise the CJTF. BOYES recruits wear uniforms (see Figure 3), are trained by the military and other organisations, are permitted to carry arms, and receive a monthly stipend of 20,000 Naira (approximately 45 USD). BOYES is structured into units. These include the rapid response squad and special forces, which collaborate, through joint tactical operations, active combat and patrols, with the military and the police. Other units, such as the agro-rangers, work with the NSCDC to protect farmers against attacks by the insurgents. The neighbourhood watch unit of BOYES primarily targets the enforcement of order and crime control at the neighbourhood level and in public spaces. The creation of BOYES has, however, left many volunteers feeling excluded from what they perceive to be the “reward package” for privileged members of the CJTF.

Figure 3: ISP uniforms and other paraphernalia

The remit of the activities of the ISPs is broad. It covers everything that the community leaders and informal security providers define as crime or misdemeanour, based on the law, religion, morality or culture. For instance, BOYES officials usually apprehend and give (unsolicited) haircuts to males with dreadlocks or “unacceptable” hairstyles. This practice is a form of moral policing and could be viewed in other contexts as a violation of citizens’ fundamental human rights.

The ISPs secure communities and public places by providing routine surveillance services, controlling crowds at events, gathering intelligence (a role also played by female members), dispersing male and female youths seen “hanging out” when darkness falls, closing brothels, resolving disputes, including domestic conflicts, and preventing the occurrence of crime. Offenders are usually apprehended and punished by the ISPs. At other times, they are handed over to the police, the NDLEA, the military or the NSCDC, depending on the crime committed and the proximity of the formal security institution.

Our analysis shows that the ISPs go by different names but basically perform similar and overlapping roles. Some residents could not differentiate the ISPs, but it was evident that the CJTF had gained more prominence than the other groups.

Informal security providers in urban security: Yes, no or maybe?

The level of engagement with the ISPs in Maiduguri varies from one community to another, depending on residents’ experiences with the ISPs. In three of the five communities studied, residents were more likely to report crime incidents first to the traditional rulers or the ISPs, while in the other two communities, residents were more inclined to report crimes directly to the police.

Residents expressed dissatisfaction with the ways in which the police handle cases and persons reported to them. For instance, they reported that offenders are often released without investigation and prosecution; and the police do not investigate a reported crime if they consider the crime “trivial” or if there is no prospect of getting some “kickback”.

In a similar vein, the ISPs have also been accused of perpetrating and enabling crime, sometimes in connivance with military or police officers. Some residents also alleged that the ISPs are brutal in dealing with offenders and often display favouritism, especially when their members or relatives have been involved in a crime.

Despite these negative reports, the ISPs are generally perceived to be more effective than the police in curbing crime in the low-income communities. Some of the residents view the ISPs as a reliable alternative to the formal security structures.

So, do informal security providers have a place in cities?

Residents of low-income and high-income communities will answer this question differently. The privatisation of security reinforces and highlights the disparities that exist in cities. In Maiduguri, the ISPs are members of low-income communities, who must take responsibility for securing their residences, while the residents of high-income areas enjoy the privilege of living behind high fences and employing private security guards.

On the other hand, formal security institutions like the police and the NSCDC, which have direct oversight of the safety and security of people and property, have not lived up to residents’ expectations. Residents cited inefficiency and its effects, including slow response to criminal incidents, poor police–community relations, high levels of crime, low number of arrests and prosecutions, lack of trust, and corruption, which facilitate criminality. Seeing successes recorded by the incorporation of ISPs in counterinsurgency efforts, the residents have continued to rely on the ISPs for safety and security within the city.

Though reports have cautioned about the dangers of engaging non-state actors in counterinsurgency in conflict zones like Maiduguri, their contributions to urban safety and security seem undeniable. It is evident that the “informal” fills in the gap left by the inefficiencies of the state and its institutions.

Further reading

Brechenmacher, S (2019). “Stabilizing Northeast Nigeria after Boko Haram”. Working paper. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Felbab-Brown, V (2018). “‘In Nigeria, we don’t want them backʼ: Amnesty, defectors’ programs, leniency measures, informal reconciliation, and punitive responses to Boko Haram”. The Limits of Punishment: Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism, Nigeria Case Study. New York: United Nations University Centre for Policy Research.

Header photo credit: Patience Adzande

Sources: Figures 2 and 3 are drawn from the author’s fieldwork, August 2022.

Note: This article presents the views of the author featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.