By Tom Goodfellow, University of Sheffield, co-lead of ACRC’s land and connectivity domain research

The urgency of developing more effective mechanisms to capture rising land values for urban infrastructure and services is now widely acknowledged. It is also accepted that this is highly challenging; as well as facing numerous bureaucratic obstacles, urban land management is entwined with processes of political and economic bargaining, and there are often intense efforts by non-state actors (including brokers) to capture large portions of land value for themselves.

A recent ACRC workshop in Accra on property taxation, linked to earlier work in the land and connectivity domain, highlighted the ongoing importance of effective valuation. Valuation itself faces numerous technical and political challenges: accurately recording land and property values can be expensive, technically complex and subject to all kinds of interference. In many countries, taxing urban land is so fraught that only the buildings on it are valued, leaving a substantial part of property wealth untouched.

In order to unlock land values as a tool of redistribution, it is important to understand what actually shapes them, and which factors stimulate land value change. Why do some areas of a city – or some specific plots of land – become so much more valuable than others? This matters, because the legitimacy of land value capture is rooted in certain assumptions about how value is created. These assumptions have proved to be questionable in many African cities.

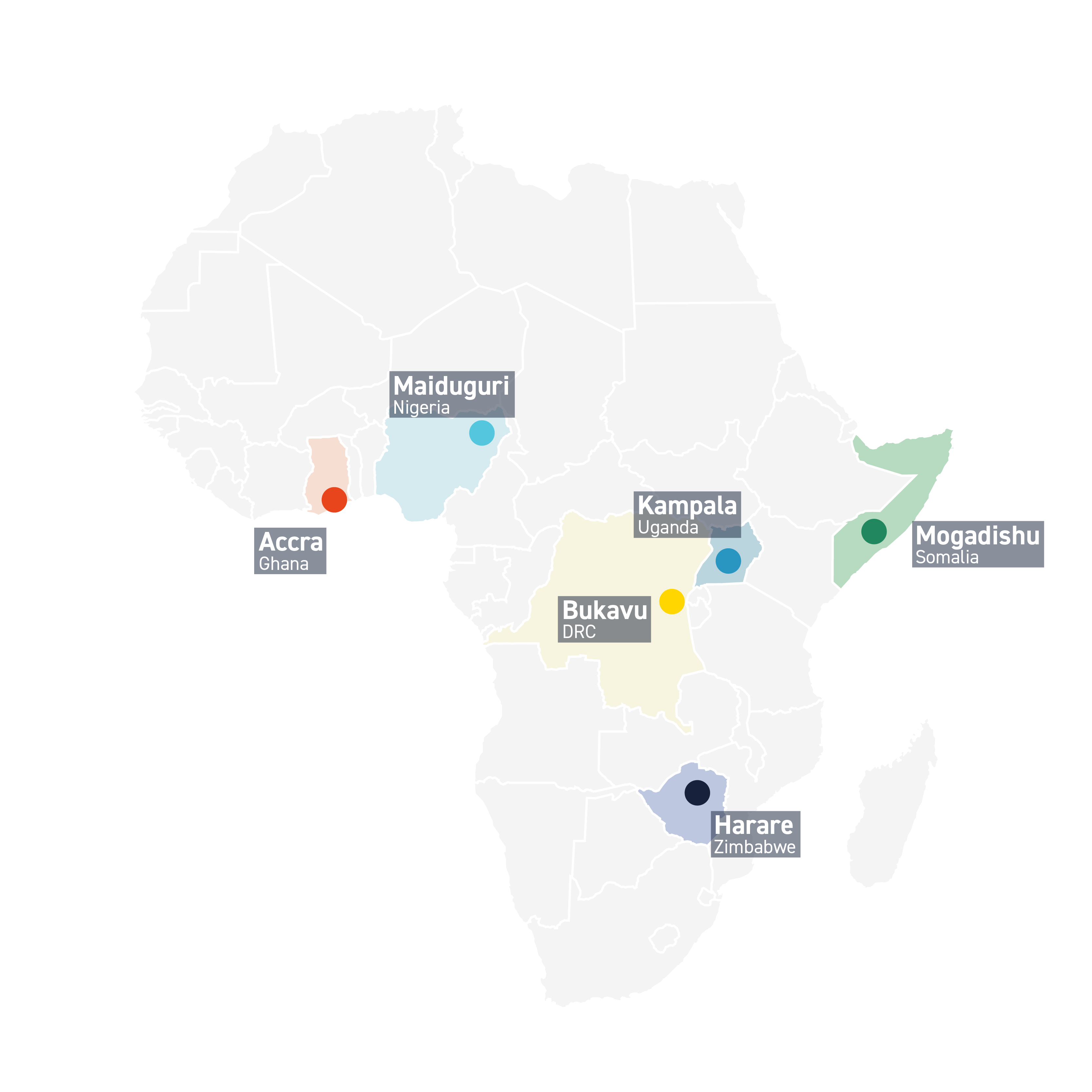

Our collective work in the land and connectivity domain report highlighted some of the actual drivers of land value change in the cities we examined: Accra, Bukavu, Harare, Kampala, Maiduguri and Mogadishu. Here, I build on this to consider how these findings challenge some of the dominant notions on which ideas of value capture are based.

“Paradigmatic ideas” about land value change

Answers to the question of what shapes land values might seem obvious, and there are plenty of proposed mechanisms posited in the disciplines of economics and planning, based largely on the experiences of advanced industrial economies. In the language of ACRC’s conceptual framework, a set of “paradigmatic ideas” dominates assumptions about land value change and feeds into policy discourses, both internationally and at more local levels.

These paradigmatic ideas depend heavily on a distinction between private property as the main site of value, and public infrastructure and public regulation as primary drivers of that value.

The received wisdom is that (private) land value increases are largely driven by three factors:

1. Increased economic activity or prosperity in an area, which inflates demand for the land

2. Public infrastructure investments that make the land more desirable

3. Changes to planning permission/regulations that again increase its desirability and therefore value

The logic, then, is that for factors 2 and 3, the uplift in value is caused by the state – by public infrastructure and regulation – and therefore it can legitimately be recaptured by the state for redistribution.

Unsettling the received wisdom

But what if much of the infrastructure provided to service urban land in an urban area is not public, but rather provided by private (and often informal) providers? What if regulations about what can and can’t be built in an area are determined less by the state than by other kinds of authority? And, moreover, what if the land in question is not straightforwardly “private”, such that any official owner being taxed also has to contend with paying a range of other levies related to more collective territorial claims on the land?

Our research revealed such dynamics in a number of cities. It suggests that the paradigmatic ideas do not represent the whole story about drivers of value change, and that context-specific institutions and practices are central. Attention to contextual “price signals” has often been present in land rent theory and the “hedonic modelling” used by real estate researchers and analysts – yet this often gets lost in contemporary value capture discourses, and such models also miss some of the most important factors in the cities we studied.

Aerial view over Maiduguri, Nigera. Photo credit: IRC

The real drivers of land value change: Findings from the land and connectivity domain

Our studies unsettle this assumption that urban property is primarily private and infrastructure is primarily public. This is particularly true if we consider property development in peripheral or suburban areas, which is taking place across many African cities.

Let’s first consider the idea of private property. In a city such as Accra or Lagos, individual property rights and heightened land commodification are very real, but co-exist and overlap with “customary” forms of tenure. Thus, while sales to individuals are common, various other actors continue to make claims to benefit from the land’s use, often based on longstanding collective ancestral rights. A share of any increase in the value of this land is therefore seen as rightfully belonging not just to the official owner but also a range of (often quite diffuse) actors. In Accra, for example, various categories of “land guards”, with varying degrees of popular and historical legitimacy, claim fees and levies for different stages in the development of property on land.

When land retains these social and collective attributes, focusing just on the property relation – for example, through taxing the owner – without attention to these other dynamics, it can result in feelings of “over taxation” and illegitimacy.

When it comes to the question of infrastructure provision and regulation, the picture from our cities also diverges substantially from the paradigmatic ideas. While major public infrastructure such as roads does often substantially bolster land value, in other cases the opposite occurs. In examples from Maiduguri and Kampala, certain road investments appeared to dampen or even reverse local rises in land value, due to having adverse impacts on personal security (such as if the road becomes associated with a rise in violent criminal activity, for instance), local population mobility, or the functioning of other infrastructure.

Moreover, the kinds of infrastructure that did significantly increase land values was often privately rather than publicly provided. In Mogadishu, for example, certain new suburbs were served with privately provided roads as well as private services such as schools, hospitals and green areas, all of which boosted land values. In peripheral areas of other cities, including Harare and Accra, the role of private actors in providing infrastructure – and sometimes also planning and regulatory services of various kinds – tells a broadly similar story.

Implications for urban reform

These findings must give us pause when thinking about appropriate routes for capturing land values. The idea of public interventions to boost (and recoup) privately held value makes less sense when, in practice, private interventions have been generating much of the value. Meanwhile, taxing land value is not straightforward in cases where it has not simply accrued to an identifiable private actor.

This is not to say that efforts towards property taxation and other forms of value capture should not be pursued. Indeed, they remain urgent. But as well as building government capacity to register values and collect taxes, there need to be ongoing efforts to build understanding on the moral and political principles underpinning property taxation, and public dialogue acknowledging the challenges people face paying tax alongside levies to non-state actors. These efforts need to be accompanied by incremental improvements to public infrastructure provision.

As so much of ACRC’s work had demonstrated, successful urban reform is rooted in trust, collective mobilisation and the building of reform coalitions. This is as true of property taxation as any other urban domain, and the better we understand the nature and drivers of the value to be taxed, the more likely that a collective agenda to redistribute this wealth will materialise.

Explore further:

Header photo credit: Barnabas Lartey-Odoi Tetteh / Unsplash. Accra cityscape.

Note: This article presents the views of the authors featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the African Cities Research Consortium as a whole.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.