Unpacking the ACRC approach

This is the third in a series of blog posts exploring the African Cities Research Consortium’s conceptual framework. Building on our first working paper, our research directors delve deeper into the urban development challenges we are seeking to address, our research approach and the concepts we’ll be using.

The first article explored the key challenges facing African cities and opportunities for development, the second introduced the consortium’s research approach and this third one looks at political settlements analysis.

By Tim Kelsall, co-research director of the African Cities Research Consortium

What on earth is a political settlement?

A political settlement can be defined as an agreement or common understanding among powerful groups within a society about the basic rules or institutions of the political and economic game. Such institutions provide opportunities for those groups to acquire a minimally acceptable level of benefits, thereby preventing a descent into all-out warfare.

The analysis of political settlements is, to a large extent, an attempt to explain how that relationship between powerful groups and institutions shapes war, peace, and development outcomes, enriching some people and destroying the lives of others, and how, if at all, those outcomes can be improved.

Settlements and the city

Over the past decade or so, scores of authors have produced hundreds of political settlements analyses of problems ranging from industrial policy to women’s empowerment; but with only a few exceptions, those studies have lacked an explicit urban focus. This is surprising in some ways, since large cities are often crucially important to national-level politics as sources of political legitimacy or dissent, economic dynamism and rent.

ACRC aims to rectify this oversight. It will apply political settlements analysis to a study of urban systems and development domains, and use it to help understand and solve complex problems in African cities.

It will bring to the table a set of distinct conceptual tools. The first is what we call a “tri-bloc” approach to mapping the configuration of powerful actors. Here, we ask which groups are nationally powerful, in the sense of being able to change or disrupt the settlement – are they gender groups, ethnic groups, occupational groups, religious groups, armed militias, street gangs, or some combination thereof? How do these groups align with the country’s de facto leader to form different “blocs”? Are they “loyal”, “contingently loyal” or in “opposition” to him or her? How strong are these blocs relative to one another? How internally cohesive are they? What strategies does the political leadership use to incorporate them into or under the settlement? And on what rents or resources does it rely?

Then we ask the same sorts of question at the city level. Who are the city’s powerful groups, who are its marginal groups, and how do they align with the city’s de facto leader? How are these groups integrated – or not, as the case may be – into national-level power blocs? What sources of rent and legitimacy do they bring? And what are the implications for the governance of urban development?

Looking over Mogadishu, Somalia. Photo credit: Jan Wellmann / Getty Images

Solving complex urban problems

Put differently, by answering these questions, we expect to gain a better sense of how national and urban political power are intertwined, the systems and domains they feed on, and how they combine to make possible the resolution of some urban problems and make probable the perpetuation of others.

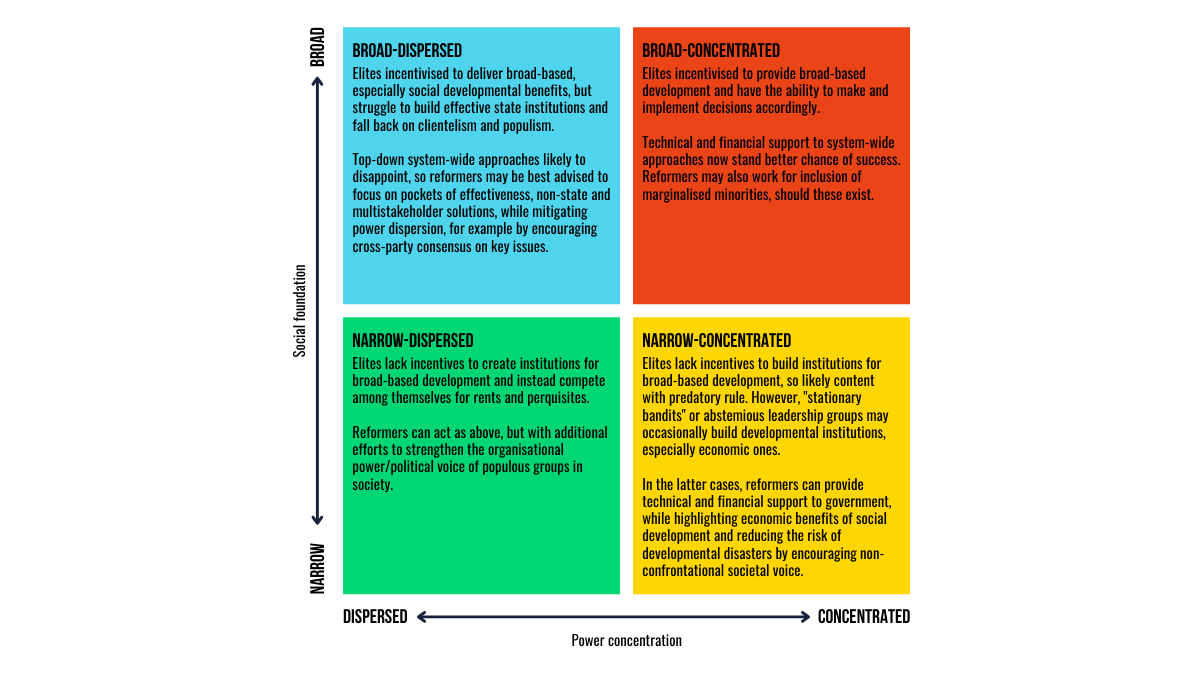

Answering these and other questions also allows us to map what we call the settlement’s “social foundation” (the powerful “insider groups” that make up the settlement), and to identify groups that are effectively excluded from, or marginal to, the settlement. In addition, it helps us to map what we call the settlement’s “power configuration” (the degree to which power is concentrated in the country’s top political leadership). These mappings yield a 2×2 typology and a set of working hypotheses about how the breadth of the social foundation and degree of power concentration influence elite commitment to, and state capacity for, inclusive urban development policy. Figure 1 illustrates this typology.

Figure 1: Political settlements typology

Putting together an analysis of the political settlement, city systems, urban development domains and our typological theory will, we hope, provide insights into where the greatest opportunities for progressive urban change lie, as well as pointers for whom to work with, when, and how.

Learn more about ACRC’s research approach in our working paper: ‘Politics, systems and domains: A conceptual framework for the African Cities Research Consortium’.

Header photo credit: Abenaa / Getty Images. Kroo Bay informal settlement in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.