Unpacking the ACRC approach

This is the fourth in a series of blog posts exploring the African Cities Research Consortium’s conceptual framework. Building on our first working paper, our research directors delve deeper into the urban development challenges we are seeking to address, our research approach and the concepts we’ll be using.

The first article explored the key challenges facing African cities and opportunities for development, the second introduced the consortium’s research framework, the third looked at political settlements analysis, and this fourth one explores the thinking behind our city of systems approach.

By Seth Schindler, co-research director of the African Cities Research Consortium

Too often, the daily reality of African cities is characterised by the failure of systems to offer basic services. Take affordable transport or high-quality healthcare, for example – or by how the poor integration of systems leads to failures of both performance and accountability to users.

The promises and pitfalls of urban development in Africa are strongly influenced by the capability of particular city systems to operate in an effective manner, and deliver equitable and sustainable outcomes.

By approaching cities as systems, researchers have been able to evaluate and compare their use of energy and other resources, which has in turn informed interventions aimed at enhancing efficiency and sustainability. However, this approach risks naturalising their contingent characteristics – for example, social and economic.

Understanding material and social systems

Within ACRC, we seek to avoid these criticisms in two key ways: by complementing an understanding of cities as systems with a political settlements framework and political economy approach; and by focusing on a number of social as well as material systems.

So, rather than a single integrated system of flows and stocks, we propose a “city of systems” approach that accounts for a series of interrelated systems, including those geared towards managing material flows (such as water and energy systems), and those designed to foster social outcomes (such as education and healthcare systems).

Our analytical framework shows how systems have been shaped over time by politics, social relations and struggles, cultural preferences, technical expertise, economic constraints and environmental factors – such as the availability of resources.

We will begin our research by grounding the analysis of each city in historically informed scholarship that identifies the choices, events and geography that have shaped the particular configuration of its systems. This will account for infrastructural path dependency from the colonial era that, in many instances, has locked-in particular development trajectories that continue to influence resource access and the built environment to this day.

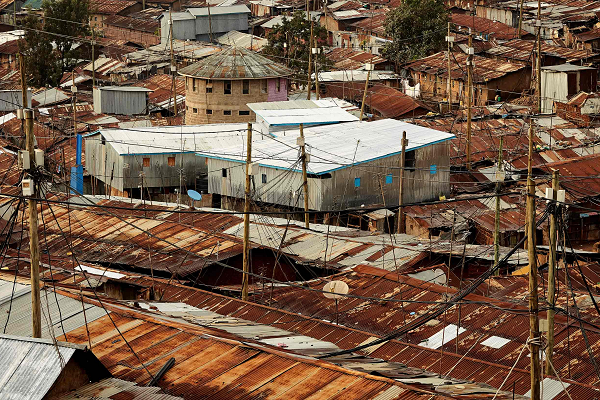

Informal residences in Kibera, Nairobi. Photo credit: Lou Bopp / Getty Images

Local contexts, local politics

The systems of African cities tend to differ from their OECD counterparts in important ways, so research methods and theoretical assumptions must be adapted accordingly. Most urban planners embrace the “modern infrastructural ideal”, in which citywide systems provide near-universal access to resources and services.

The basic unit in this ideal type is the single-family dwelling, which serves as the interface between individual residents and material flows (such as access to water and disposal of solid waste). Most African cities do not conform to this ideal, for example, with multi-family occupancy in rental units on a single plot, and in this context their systems tend to be characterised by fragmentation and heterogeneity

To add to this, a city’s systemic profile is shaped by political and technical choices that powerful stakeholders have made – about whether to either incinerate solid waste or inter it in a landfill, for instance – along with the availability of resources, and demands from residents for infrastructure, resources and services. In this way, the evolution of a city’s systemic profile is driven by social relations and political contestations that operate at multiple levels – on street corners and in neighbourhoods, as well as at national and international scales – and in relation to particular domains that incorporate multiple systems.

An account of urban processes in African cities requires not only a deep understanding of the political settlements, but also the (often informal) mechanisms powerful stakeholders use to extract rent through their control over city-based systems, and strengthen their hold over power and/or means of economic accumulation.

Waste recycling provides employment opportunities for residents in the Agbogbloshie area of Accra, but presents health and safety risks. Photo credit: JoseCarlosAlexandre / Getty Images

Vulnerability and resilience

Systems within cities are subject to exogenous shocks and stresses, which can originate in immediate hinterlands or in places around the world with which cities are connected. Indeed, political upheaval, social unrest, economic crisis and environmental catastrophe can reverberate in cities around the world.

Most recently, Covid-19 demonstrated how quickly localised epidemics can become global pandemics. In addition to its impacts on health, Covid-19’s prolonged interruption of supply and demand for many goods heralds a looming global economic crisis. City-based interest groups seek to limit their exposure to exogenous risks, but as Covid-19 demonstrates, it is impossible to mitigate risk completely.

Many economic, social, environmental and political shocks and stresses constitute push-factors that increase rural-to-urban migration. City systems therefore must be adaptable enough to accommodate increased demand from rural migrants – or reduced demand from urban citizens returning to rural areas – sometimes at very short notice, as a result of conflict or natural disasters, and/or for brief periods (for example, daily commuters and seasonal migrants).

Framing the complexities of city systems

In summary, many factors establish the parameters of possible systemic configurations. In addition to political settlements, such factors include geography, the availability of resources, lock-in, path dependencies, citizen agency and protest, as well as exogenous influences. Additionally, systems are shaped by practices, both governance and organisation “from above”, and “from below” by users who seek to access and maintain systems.

Understanding cities as complex systems offers the potential to identify needs, plan interventions, and anticipate or evaluate impacts in a more holistic way, that recognises the intensely interrelated character of cities and their constituent parts.

Learn more about ACRC’s research approach in our working paper: ‘Politics, systems and domains: A conceptual framework for the African Cities Research Consortium’.

Header photo credit: TG23 / Getty Images. A busy street in Accra, Ghana.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.