Unpacking the ACRC approach

This is the fifth in a series of blog posts exploring the African Cities Research Consortium’s conceptual framework. Building on our first working paper, our research directors delve deeper into the urban development challenges we are seeking to address, our research approach and the concepts we’ll be using.

The first article explored the key challenges facing African cities and opportunities for development, the second introduced the consortium’s research framework, the third looked at political settlements analysis, the fourth explored the thinking behind our city of systems approach, and this fifth one explains the concept of urban development domains.

By Diana Mitlin, CEO of the African Cities Research Consortium

There is a widespread recognition that narrowly focused sectoral urban interventions tend to fail.

Sectoral interventions are particularly likely to fail in the urban context because of the inter-relationship between consumption and production of goods and services. The presence of multiple agencies and organisations – and complex norms, values and practices, which have an overlapping presence on the ground – exacerbates problems. Improvements in one sector frequently have unanticipated impacts in other sectors that may mean the intervention is ineffective, and can potentially create other difficulties.

For example, improved water services are about much more than just laying down pipes and collecting payments for installation and water services. Pipe installation may require regularisation of informal settlements – where between 50% and 90% of urban residents live – and the re-blocking of existing dwellings (to enable pipes to be laid). The lowest income households may find they cannot afford regularisation costs, some residents may be displaced because of re-blocking of plots to ensure that paths follow straight lines and enable pipes to be laid, and tenants who cannot afford associated rent increases may have to relocate to other neighbourhoods.

Installing water pipes is particularly complex where land is privately owned. In terms of water services, regardless of who owns the land, existing informal providers may block utility provision because they lose their livelihoods – and there may be complex negotiations required for installation to continue. With the shift to utility supplies, households may be required to pay connection fees to benefit from supplies directly to their dwelling or plot. And water can only be safely supplied at the household and neighbourhood level if there is also drainage to remove waste water that needs to be disposed of.

Beyond sectoral interventions

ACRC’s analytical framework uses the concept of urban development domains to transcend both sectoral and traditional systems-based thinking, and to recognise that forward-thinking agencies, alliance and reform coalitions have long moved beyond sectoral thinking.

Domains enable us to drill down into sub-city processes, relations and institutions, recognising that the political economy and systems failures vary across domains. ACRC domain studies will be comparatively analysed between domains, and between individual domains and city-level analyses, to deepen our understanding of outcomes.

There are links between our notion of domains and the idea of a “politically-informed multi-sectoral approach”. However, we prefer the term domain because it draws attention to issues of power and authority as ideas about domain reforms are tested and challenged, and better represents the epistemic communities that emerge around specific domains.

Alongside helping us to see the politics of urban development challenges (which are tied to how particular actors frame problems and mobilise around their solutions) domains also help us analyse outcomes and opportunities across the political economy and city-of-system dimensions of our framework.

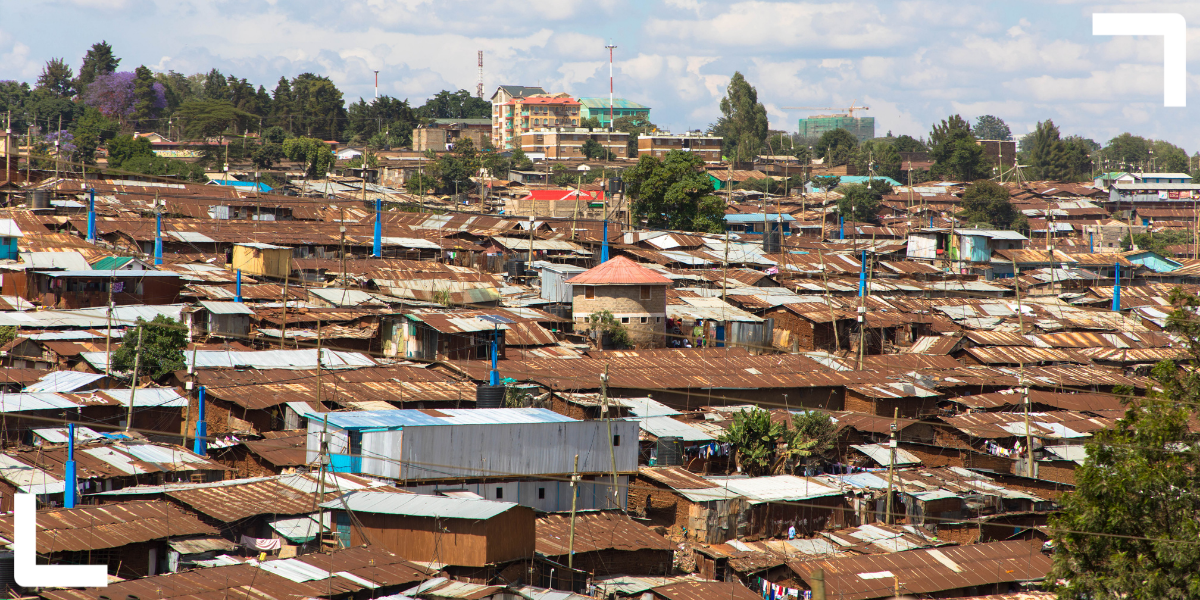

Housing in Kampala, Uganda. Photo credit: Ryan Faas / Getty Images

Defining domains

Domains are fields of power, policy and practice that are relevant to solving particular problems and/or advancing specific opportunities in relation to cities. They are constituted by actors (political, bureaucratic, professional and popular) that seek to claim control, influence and rights over a particular field – such as housing or the contribution of cities to national development – through various means.

Urban development domains are multi-scale and multi-system. Systems interactions help to define what can be achieved by programmes and projects that take place within a given domain. Take the domain of housing as an example; housing improvements can only be secured through improving the performance of water and sanitation services, and ensuring the provision of housing finance.

Housing is also an illustration of the importance of multi-scalar improvements. Residential neighbourhoods need to be connected to other residential areas. Residents need to be able to maintain and develop social and livelihood networks. And the density and compactness of a city affects its contribution to climate change, and to climate change adaptation strategies.

Urban development domains play diverse roles in sustaining the wider balance of power at both city and national levels – for example, providing rents, controlling electorates and/or providing legitimacy to governing elites in ways that in turn shape how authority is contested within domains, and whose interests and ideas predominate. The objectives of urban development domains are part of what is contested. Returning to the example of housing, should housing developments represent the modernisation ideal or should they favour lower cost, incremental style development?

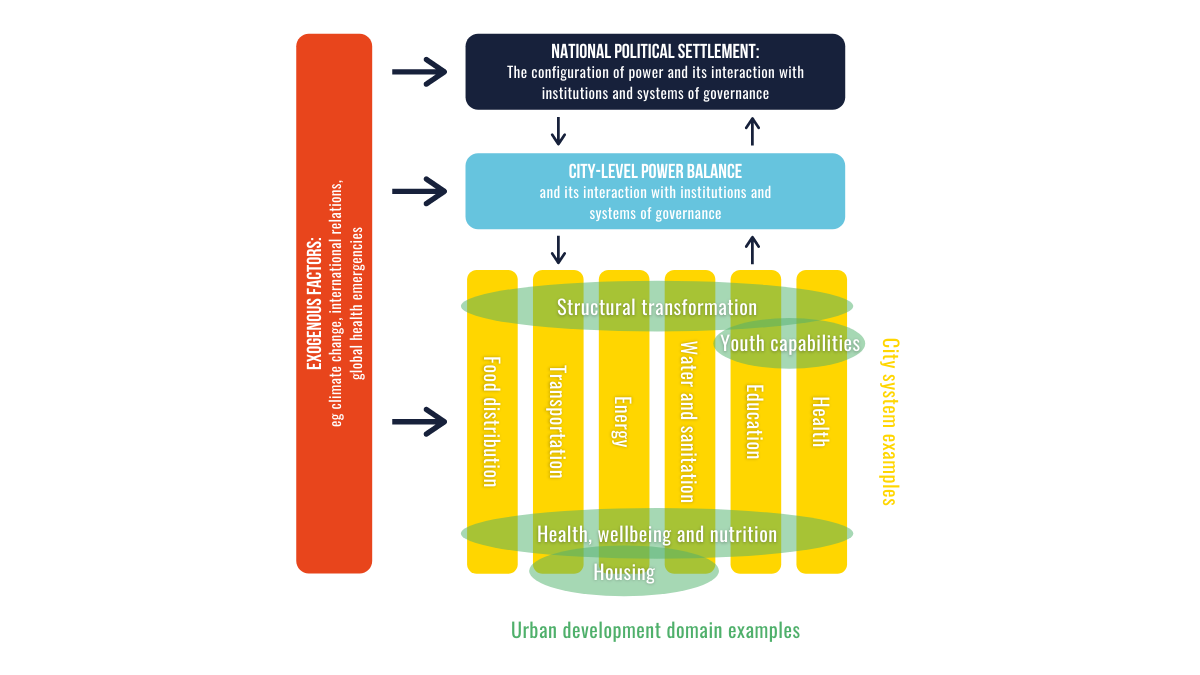

Figure 1: How domains (in green), sit alongside systems and political settlements analysis

Collective knowledge and action

A particular feature of urban development domains, and policy domains more broadly, concerns the role of epistemic communities, defined by Peter M. Haas as: “… a network of professionals with recognised expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area”.

Domain-level actors draw on and further strengthen epistemic communities to expound particular ideas, build strategic alliances or coalitions to achieve strategic objectives, and undertake direct activism, policy reform, new programming approaches and reformulated practices to solve problems and advance opportunities. They provide platforms for contestation, as ideas are tested and refined. Such epistemic communities reach beyond national borders, linking those aspiring to change local outcomes with evolving professional approaches, new academic insights and wider ideologies with which to engage.

Domains are highly political because they involve validating specific forms of intervention and their direction of travel. Expertise is central to this process, and what is legitimated by the expertise within domains potentially affects elite interests in multiple ways, such as, the ability to secure electorate support. Domain platforms enable ideologies to compete for dominance, and personal and political interests to be challenged and/or advanced.

Collective action on the part of those excluded from and/or adversely affected by domain-related processes may challenge the way in which domains function, especially if well-placed members within the epistemic communities take up these causes and represent these voices, and this may lead to reforms. For example, resistance to the demolition of informal settlements has encouraged the growth of informal settlement upgrading in at least some locations and organisations of informal workers have challenged both market-based processes of exploitation and state policies and programmes. Hence, domains are sites of contestation between actors with different interests and ideas, and different levels of holding power within the broader political settlement.

ACRC’s urban development domains

ACRC’s task is to understand how to intervene through policy, programmes and practices to improve inclusive development outcomes in cities.

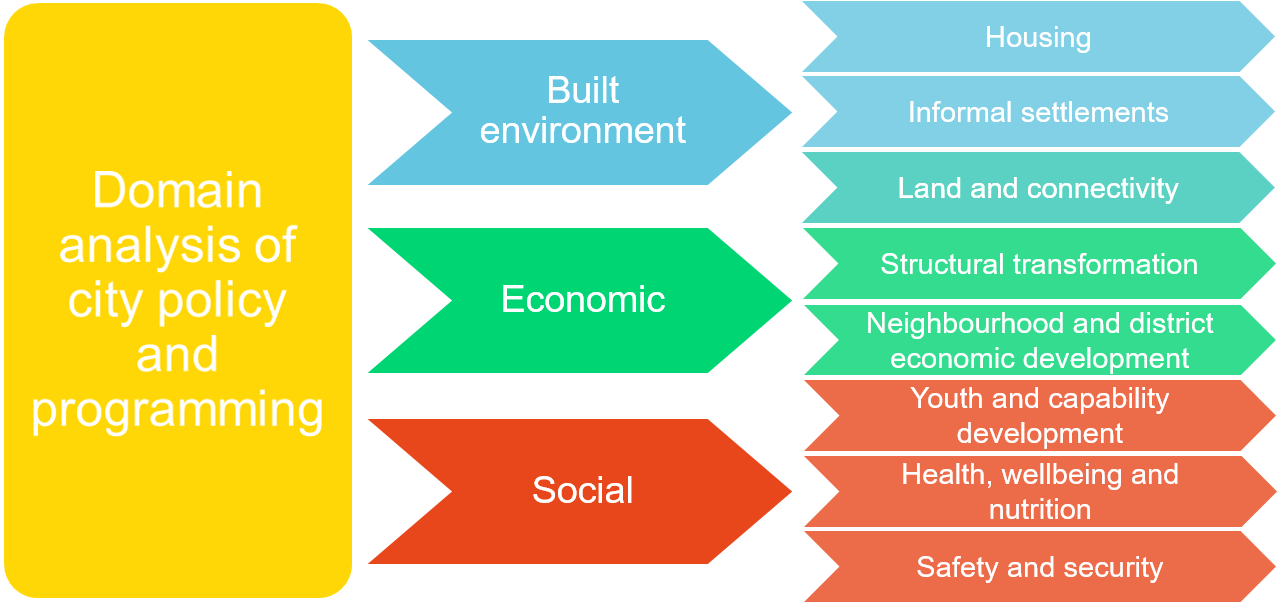

The extent and ways in which domains perform political roles for powerful interests within the settlement will influence what is possible within them. The way in which the domain is configured (in terms of the balance of power between different actors, and the kinds of knowledge and ideas that are therefore privileged) will suit certain interests and problems, whilst also preventing other problems from being resolved in ways that secure more equitable and sustainable forms of development. ACRC is working with eight domains, which fall into three sets:

- Built environment domains that also play important economic and social roles;

- Housing

- Informal settlements

- Land and connectivity

- Economic domains that focus primarily on income and asset generation;

- Structural transformation

- Neighbourhood and district economic development

- Societal domains that affect all citizens and their efforts to secure health, wellbeing and opportunity.

- Youth and capability development

- Health, wellbeing and nutrition

- Safety and security

Figure 2: Domain categories

We have identified a set of domains that reflect both the needs of low-income and disadvantaged groups, and the priorities of city governments. They also reflect the interests of a range of national and international development agencies that have invested in programmes to address urban development priorities.

We’ll be studying three to five domains in each of our 13 focus cities. In addition to providing vital insights into the complex problems they are facing, this will also enable us to explore cross-city comparisons of domain processes, and outcomes.

As we move from our initial research on urban challenges, towards action research to address those problems in the next phase of ACRC’s work, knowledge of domains – and established relations with domain actors – will help to ensure a high quality of design for solutions to the priority complex problems, and the uptake activities around those solutions.

Learn more about ACRC’s research approach in our working paper: ‘Politics, systems and domains: A conceptual framework for the African Cities Research Consortium’.

Header photo credit: Eisenlohr / Getty Images. Kibera informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya.

The African Cities blog is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means you are welcome to repost this content as long as you provide full credit and a link to this original post.